As the need for video and other online learning resources becomes more important, empowering students to create their own rich media offers a great way to generate learning resources and place students at the centre of their own learning. In higher education, the use of videos has traditionally been consumptive, with the focus being on teachers using video for additional content delivery or flipped learning. However, there is currently an interesting shift from ‘consumption’ to ‘production’ taking place in higher education, where students are now being asked to generate their own digital multimedia as a form of (mostly) summative assessment.

This article was contributed by Sam Clarke, Sue Atkinson, and Danny Liu.

Why video?

Video can be a great way to embrace student-generated content in your teaching. Getting students to create videos and other rich multimedia resources may open up new forms of assessment, innovative learning activities, and opportunities for peer learning and engagement. Producing video content can be an effective way for students to learn and can lead to a number of benefits, including the developing graduate qualities, improved final exam performance, and building an ongoing resource for student learning. Some even see video assignments becoming the new ‘written report’ in years to come. Student-generated media projects can support students in exploring rich and authentic learning environments that may even take them be outside the lab or lecture hall.

How are people using student-generated video in their teaching at Sydney?

After an excited burst of discussion on Yammer, we went around the University to ask staff how and why they use student-generated video in their units. Here’s what they said, and their tips for anyone wanting to explore this approach.

A/Prof Chris Roberts and Christie Van Diggele, Medicine and Health

Chris and Christie find student-produced video an excellent way for students to demonstrate attainment of complex learning outcomes, such as interdisciplinary effectiveness. They use it for the Health Collaboration Challenge, an annual University event which unites around 1700 students from dentistry, oral health, nursing, medicine, pharmacy, occupational therapy, speech pathology, physiotherapy, dietetics, diagnostic radiography and exercise physiology in a shared activity. Inter-professional student teams of 5-6 students are required to submit a 5-minute video on the management of a complex patient case as a part of their formal assessment. They are also required to peer mark two videos which provides them with insight into how other teams managed their patient case. Students are guided through what is required on their online unit of study site through the use of a pre-module which provides examples of past video submissions and how to peer assess. They also provide students with a video guide sheet (download it here), video marking rubric (download it here) and FAQ page.

The team-based creation and review of student-produced videos both demonstrates inter-professional learning outcomes and is in itself a team building task.

Teams meet up on the Health Collaboration Challenge day to work on their video together, often completing the final edits at home. Students are very independent in the task, usually only requiring guidance if they have an issue uploading their video (which in 2018 ended up being around 2 teams of the 282 submissions). The final videos display student competencies in teamwork and collaboration, but also in creativity and innovation.

Chris and Christie’s tips for academics wanting to try student-generated media:

- Prepare students well for the task.

- Having a meaningful assessment plan that is well communicated.

- Encourage good sound quality.

- Use the existing wisdom of the University community in making the most of Canvas

- Go for it!

Prof Peter Thorn, Medical Sciences

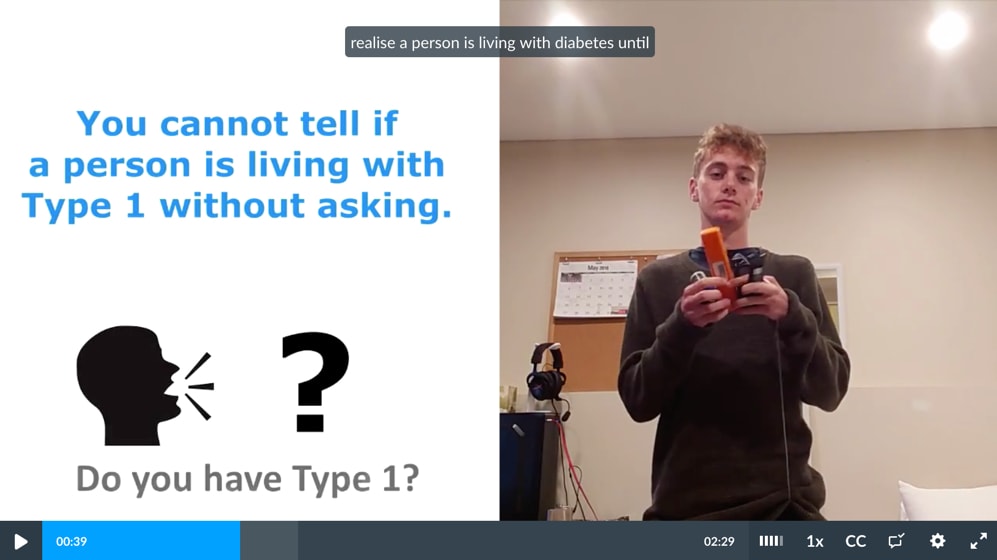

Peter uses video assessments in his OLET1504 – Health Challenges: Diabetes. In his video assignment, Peter aims to generate authentic tasks that exploit the students’ knowledge and get them to put this knowledge to work in a novel way. “As part of the on-line OLE environment I wanted to use media appropriately as an assessment tool. I use both podcasting and videography. My main aim is to add depth to the tasks so that students have to reformulate their knowledge as part of addressing distinct scenarios.” These scenarios have included ‘Make a video that explains changes you have made to the workplace that specifically reduce the risk of getting type 2 diabetes’, and ‘Make a promotional video that is targeted towards potential cash donors that explains the background to the disease and how funding in biomedical science would be directed to help further understanding.’

they [students] came up with imaginative media content and delivery that has a solid grounding

The marking rubric (download it here) is more focused towards the narrative and the response rather than the content. Peter builds up to the video assessment with prior assignments. For example, he gets get students to first make a 1 minute podcast in response to an authentic task, so students start to become familiar with the process of producing multimedia content. He found that most students really rose to the challenge saying, “they came up with imaginative media content and delivery that has a solid grounding in the knowledge they have gained in the unit. This is self-evident in their outputs.” He mentioned that the technology does put some students off, but had some tips for those starting out:

- Narrative is really important in any media, as is progression of assessments.

- Generate questions for the video assessment that are authentic and lend themselves to being addressed in a narrative structure.

- Scaffold the technology so that students get progressively used to making multimedia.

A/Prof Patrice Ray, Geosciences

Patrice introduced a group exercise to 3rd year Tectonics students to design and build a website on a theme relevant to their unit, and then present a 15 minute talk on this. However, he soon changed this to a 5 minute video exercise after students reported that the talk was “very unpleasant”. Having done video assignments for over a decade, Patrice hasn’t looked back. “My experience is that students are having a lot of fun putting these videos together. Early on, access to the right technology was an issue, but with the video recording capability of smartphones this is no longer the case.”

He runs the video assignment exercise during the second half of the semester. He asks students to organize themselves into groups of 3 (no more to mitigate free riders), who then select a topic from a list he provides in week 6. From then until week 8, each group gathers and processes information, and designs the storyboard for their video. These are reviewed during a 20 minute meeting with Patrice in week 9, after which students produce the videos and present them to the class for peer assessment.

this is a great opportunity to discuss and correct the many misconceptions that may have gone unnoticed

“I would say that this is a great opportunity to discuss and correct the many misconceptions that may have gone unnoticed. It is also clear that information, knowledge and learning are more deeply encoded, and I am reasonably convinced that this kind of exercise promotes deeper learning, in part because there is a strong element of social interaction around the process of creating a video.”

Patrice’s tips for those wanting to explore student-generated videos?

- Keeping in touch with each group and providing guidance is critical, since time management is key to the success of this exercise.

- As it is a group assignment, let students assess their own contribution to this group exercise, and modulate the mark accordingly.

Dr Ilektra Spandagou, Education & Social Work

Ilektra coordinates the unit Disability Awareness and Inclusivity which has an individual student generated video as its major assessment piece. She has incorporated the best student videos into the unit content (with permission) and says that drawing on the expertise and interests of students to generate content that she couldn’t write herself was always an aim. She cites as an example a video created by a student on an Xbox Adaptive Controller for people with a disability. Some of the other videos students have produced have drawn on their personal experience of disability which also adds to the richness of experiences in the unit.

It was always an aim to draw on the expertise and interests of students to generate content that I can’t write myself.

In addition to presenting the 2.5 minute video on a topic around accessibility and inclusion, students have to be inclusive in their presentation and incorporate technical accessibility features such as captioning and descriptions of key visual elements. Ilektra supports the students through clear assignment instructions, help with topic selection through a discussion board, a rubric, plus short workshops and ‘cheat sheets’ on technical elements. She also provides a sample video she created that has a combination of good and poor elements which students ‘unpack’ to support their own planning.

Many students have relished the opportunity to research and critically assess an area of disability and inclusivity that interests them, to apply their understanding to a real world issue and act as advocates for a more inclusive culture and society. The quality of work produced has been very high and Ilektra’s tips for academics wanting to try student-generated media are:

- Remind students to ensure their presentation is inclusive and to consider accessibility by including closed captioning.

- Don’t be tempted to allow students to create long videos.

- Support students to aim for a standard that can be shown to others.

- Provide past students’ videos to unlock more ideas for students as well as modelling styles of video and the variety of ways to tackle the assessment.

With the right support, she finds that they are more than capable of it.

Prof Ross Sanders, Health Sciences

In the ‘Exercise and Sport Science’ unit for the Graduate Entry Masters in Exercise Physiology, students learn about neurological disorders such as those associated with cerebral palsy, Parkinson’s disease, stroke, dementia, frailty, multiple sclerosis, traumatic brain injury and spinal injury. Students need to be able to produce exercise programs appropriate for the rehabilitation and maintenance of function, particularly for the activities of daily living. “I have found that the production of instructional videos for use in the field is both effective in developing their skills in applying the knowledge as well as being motivating and enjoyable for the students.”

Students work in groups of 3 to develop an exercise program for a client (real or fictitious) with particular functional deficits. They are required to develop and show activities for stimulating the neuromuscular system to promote learning, relearning, or maintenance of function in activities of daily living. In addition to the written report that describes the program and the activities, they produce an instructional video that can be used for disseminating their ideas to Exercise Physiologists and other health professionals for application in the field. Apart from students performing strongly against the marking rubric (download it here), Ross notes, “it is apparent that students have advanced their thinking and reinforced their knowledge by having to apply it to an actual case. Their ability to think laterally to incubate novel ways to apply the knowledge to practice became increasingly apparent as they progressed from planning to implementation.”

Ross’ tips for success?

- Emphasise the potential benefits that the video production may have for the students’ professional colleagues and their future clients, that is, it is not just an exercise to pass the unit but can have ongoing value and impact in the field.

- Have clear assessment rubrics which indicate the standards to be attained to be awarded marks equivalent to each grade (pass, credit, distinction, high distinction). Students are highly influenced by the content of the rubric and usually strive for the highest quality that they can achieve within their current levels of experience. Given that they know very little about media production techniques prior to the unit, and use very basic resources such as mobile phones, the results are impressive.

- Try to have a ‘hands on’ workshop on video production and editing conducted by an experienced expert such as a Faculty educational designer (in his case this was Sasha Cohen). This helped students to identify common problems, how they can be avoided or compensated and helped them identify good video techniques. Sasha has kindly shared the resources he provides students: tips for filming with smartphones and a storyboarding template to help design videos.

Dr Hong Nguyen, Life and Environmental Sciences

Hong coordinates a first-year human biology unit for over 1,400 students each year. In order to kickstart her students’ development of critical communication skills, they make an individual video worth 15% of their final grade. Production of the video is scaffolded, with a comprehensive set of guidelines and assessment information provided (Hong has shared these here). Students develop draft video plans, receive peer feedback on both the draft plans and the draft video and then submit the final product for marking later in the semester. They are able to choose any topic related to the unit that interests them, such as ‘Could humans ever breathe underwater?’, ‘Why do I get hungry?’, and ‘What is a cytokine storm?’, and are asked to choose an audience (e.g. peers, primary school students, the general public, etc) in order to emphasise the breadth of science communication.

Hong mentioned that her students had a mixed response to the task. Many loved the opportunity to engage with a creative assessment and push themselves out of their comfort zones. Some of her students commented, “I loved the video recording unit and processing, it was a bit challenging at first but it was great as it allowed us to express our own individual creativity so that bio wasnt just a mundane memorising subject.” and “I really enjoyed the video and processing task as it allowed us to branch out and practice communication in ways that we might not be comfortable with.” However, some students struggled to see the relevance of this to their degree or major – although she thinks this might be related to assessment load in the unit.

Hong’s tips for those considering video assignments (and also for herself as she iterates on this design):

- Consider having these as group tasks to further foster student collaboration and peer learning (and, pragmatically, to reduce marking load).

- Balance the number and weighting of assessment tasks in the unit, considering videos can take longer to produce.

- Help students see the relevance of the video to their university studies and further careers.

Dr Claudia Keitel, Life and Environmental Sciences

Claudia’s experience with student-generated videos was highlighted previously in Teaching@Sydney. She asks students to create a video about the link between chemistry and agriculture; one that would make future agriculture students excited about chemistry. Students said the assignment was fun, and that the viewing session increased their sense of community. The understanding of the importance of chemistry to agriculture was also enhanced.

It increased the students’ sense of community and created a positive learning experience for them, which I think is especially important for first-year students.

Here are some of Claudia’s tips for academics starting out – there’s more information in the full article.

- Think carefully about balancing investment and reward – producing a video can be a time-consuming task and the mark should reflect this.

- Facilitate group formation.

- Give students clear instructions about the aim of the assignment.

- Stress the importance of audio quality.

- Just give it a go!

A/Prof Joseph Lizier, Engineering

We highlighted Joseph’s story previously in Teaching@Sydney. He asks students to make short explanatory videos based on pre-readings, leading to deeper engagement and a wider coverage across the cohort. This meant that students created resources at a level that other students could easily watch and understand, while deeply engaging with pre-readings themselves. It also allowed them to gain confidence for their final case study assessment.

I found the videos gave a better platform for showing off their skills – their critical thinking was more evident verbally than in writing, and this flowed into the class discussions with increased buy-in there.

Here are some of Joseph’s tips; check out the full article for more information.

- Be clear what you want students to get out of the assignment and link it to unit learning outcomes. How does it actually contribute to the unit?

- Allow students flexibility in how they make and deliver their multimedia product. For example, give students the choice to present voice-over-slides, or as a talking head, or animation, etc.

- A clear rubric (Joseph’s example can be downloaded here) helps to speed up marking.

Dr Susan Coulson, Health Sciences

When Susan heard about student-generated media, she was convinced of the benefits of having groups of students work together on a video project with an output that could be both marked and shared with a broader audience. She designed an activity to give students a deeper understanding of physiotherapy in the management of multi-system problems within the community and to facilitate the communication of theoretical, assessment, treatment and clinical reasoning concepts in a manner that could be easily understood by the majority of the educated lay public. Student groups of 4-5 chose their topic based on one of the areas presented in lectures and tutorials, and were supported by industry mentors who had a special interest in the field they are examining. “For example, they may visit the neonatal intensive care or burns unit of a major teaching hospital, or attend a factory which manufactures and fits prosthetic limbs for amputees.” Their video was 4-5 minutes long and worth 30% of the final unit mark.

Susan notes that the assessment can polarise students. “Most really enjoy the opportunity to work with their peers to create a video that they are really engaged with and enjoy the whole creative and theoretical process. However, some students dislike this type of project as it is novel and so different from other types of physiotherapy practical and written assessments.” She runs a ‘digital media showcase’ which is held after all the other assessments are handed in – each group introduces their video which is then played in a lecture theatre. This “is also a great way for students to refresh their understanding about the broad range of topic areas covered in this unit prior to their written exams“. Susan has even presented student videos at the NSW Branch of the Australian Physiotherapy Association, and written a paper about it.

Susan’s tips for those starting out:

- Have a brief meeting with all student groups over the first 2 weeks after the assessment is commenced to enable them to ask questions and receive feedback prior to filming.

- It can take a lot of time to develop, so be really clear about what you want to achieve by implementing this as part of your unit.

How can I get started with video assignments?

Video assignments are a great way to give students choice in how they express and construct their own knowledge. Using video assignments can also be seen as part of the higher education shift towards learner-centred assessment, one where individual learners are recognised and where we as teachers move further away from didactic, teacher-focused education practices.

Why video?

If you are thinking about including video assignments into your units of study, it is important to consider:

- What do you want your students to learn?

- How will you support your learners?

- How to guide

- Rubrics

- What am I trying to assess?

By starting with these questions and considerations in mind, you will better placed to develop meaningful, constructively aligned learning tasks that both challenge and support your students.

Limitations and managing risk

Using video assignments in your units does come with some risk and there are some limitations when considering video’s utility. It is also important not to assume that students are ‘digital natives’ and they may need some help with this new form of assessment. Providing rubrics to guide and assess learners on both audio visual quality and managing inherent risks that can come with students going out into the world filming actual video footage (such as IP, privacy, publishing, and personal risk), can also be an effective risk mitigation strategy.

Tell me more!

- Check out the “Creating Educational Media” module in the University of Sydney’s Modular Professional Learning Framework to learn more about using student-generated videos for assessment and other learning, as well as the chance to get hands-on with some media equipment and experiment with different techniques that your students could use. The module pages on Canvas also have some quite impressive examples of student-generated videos for inspiration.

- Feel free to post any questions you have onto the Educational Innovation Yammer group.