Reading Beckett and Joyce with a French accent

Rabaté has been “one of the key figures in defining modernist studies and the key figure in transmitting French ideas to the English-speaking world,” said Dr Anthony Cordingley, who is the Robinson Fellow at the University of Sydney, a specialist in modernist and contemporary literature, and in translation studies.

He invited Rabaté to spend a week at the university in December 2019, hosted by Sydney Social Sciences and Humanities Advanced Research Centre (SSSHARC). The main purpose was to conduct an Ultimate Peer Review of the manuscript of Cordingley’s new monograph, Samuel Beckett and the Ends of Education, in a roundtable conversation that aimed to help the author refine his work before publication.

This was also an opportunity to hear about Rabaté’s work and relationships with important figures such as the French philosopher Derrida, the founder of deconstruction, who died in 2004.

Under the influence of Derrida

As an undergraduate student of English, German and lettres modernes at the École Normale Supérieure in Paris, Rabaté noticed Derrida’s “office hours” when he was available to students. After his first visit, Rabaté realised he was the only one taking this opportunity and began to go every week for three hours' conversation. Derrida personally knew Joyce, had read Finnegans Wake, gave Rabaté material to read, and helped to shape his career.

Jean-Michel Rabaté, Professor of English and Comparative Literature, Department of English, University of Pennsylvania

Born in France in 1949, Rabaté has spent much of his academic career in the US, and is a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. However, he said, “I became more French after moving to the United States; I discovered I was really French and I didn’t know it.”

Rabaté is Professor of English and Comparative Literature at the University of Pennsylvania, and an esteemed literary theorist. He has written and edited more than 40 books on modernism, psychoanalysis, contemporary art, philosophy, and writers including Beckett, Joyce and Ezra Pound.

Beckett, an Irishman who lived in France and wrote in English and French, has been labelled the “last modernist”. But Cordingley argues in his book that scarce attention has been paid to “his rejection of the pedagogical imperatives of high modernism – to rejuvenate the Western tradition by recasting its mythology, philosophy and classics anew”.

Cordingley outlines his premise: “Beckett’s infamous silence about his own work, his extreme reluctance to give interviews or to comment in public upon his own writing evinces his complete rejection of the role of the pedagogue or public intellectual…

“His writing, however, returns obsessively to relationships of domination and subjugation, where power is negotiated through the currency of learning, of knowing. Scenes of instruction proliferate and his narrators are haunted by the voices of their past masters. To what extent then is Beckett’s writing a teaching about teaching, about our capacities to know and to transmit knowledge?”

Was Samuel Beckett too neurotic to teach?

At the Ultimate Peer Review Cordingley asked for critical feedback on his manuscript from Rabaté, and from Sydney University scholars in literature, critical theory and languages who were invited to participate and had read the first two chapters of the book, which will be published by a leading university press.

The Ultimate Peer Review scheme is unique to SSSHARC and available to Sydney University researchers who have completed a draft of a potential landmark work. The author brings an international scholar with outstanding relevant expertise to evaluate the work both in private conversation and in the discussion group.

As the interlocutor and critical “opponent”, Rabaté praised Cordingley’s central idea about education in Beckett’s work as original, and offered comments and questions, illustrated with entertaining anecdotes. He pointed out that a quotation in the text came not from one author but from another, someone he knows and “saw last week”.

He suggested looking again at the notes Beckett’s students kept on his classes, where he was said by some to have written silently on the board for five minutes before turning to them and uttering one obscure sentence. “People say he was too shy, too neurotic to teach. Maybe not.”

Was Beckett a “Jacotot teacher”, he wondered. Cordingley’s book opens with an account of Joseph Jacotot, a French educator who proposed that “teachers should be ignorant of the subjects they teach” after his success at teaching Flemish-speaking students with no shared language.

Joseph Jacotot (1770-1840). Lithograph by A. Lemonnier after Hess. Credit: Wellcome Trust, V0003035

As author of a new book on Beckett and the Marquis de Sade, Rabaté said, “Beckett was brought up in a system that says you have to beat up students to make them learn”.

Experience also allowed Rabaté to say: “I can talk about the École Normale because I was there. Normaleans were notorious for being arrogant. They did exams not having been to lectures or classes, expecting to do well. They were hated by the other students…Foucault, Derrida and Sartre failed [entrance and other exams] many times [before succeeding].”

There were suggestions from others in the group to look further at Pound’s Cantos on education, to bring in playwright Bertolt Brecht (whom Beckett hated), to consider feminist writers other than Virginia Woolf and how educational institutions excluded women. Cordingley accepted or defended the points made in a productive discussion.

In his book, Cordingley explains why new perspectives on Beckett are emerging: “In Beckett studies valuable work in the past decade has overturned the stereotype of Beckett as an apolitical artist. The increased biographical information that became available with James Knowlson’s biography has been supplemented considerably in the past decade with the publication of four volumes of Beckett’s letters, the contents of his library and its marginalia, manuscripts have been digitized, and archives of notes from Beckett’s studies in philosophy and psychology, as well as travel diaries have yielded myriad insights and spawned a new historicizing turn in scholarship. ‘[W]e have’, as Jean-Michel Rabaté writes, ‘a new Beckett on our hands’, and this new Beckett is a much more political animal than he had ever been given credit for, more engagé than Jean-Paul Sartre ever recognised.”

The revolutionary James Joyce

“There is more work being done on Beckett than on Joyce at the moment,” Rabaté added, comparing the two francophile Irishmen. Among other reasons: Joyce scholarship is saturated and Beckett is “more modern”. Beckett had a longer and more recent career (he died in 1989, Joyce in 1941), living through World War II, witnessing the Shoah and concentration camps.

Even so, Rabaté gave a public talk at the University of Sydney on “Joyce and Critical Theory”, which was a reminder of how radical Joyce had been. Rabaté began his career in Paris as a Joyce scholar working with Hélène Cixous and among his latest work is a chapter in A Guide to Joyce, edited by Catherine Flynn (Cambridge University Press, 2020) .

He recalled attending a Joyce conference at the Centre Pompidou in 1975 at which the writer Philippe Sollers pulled the grey-brown dust jacket off Finnegans Wake – his last, most complex work, published in 1939 – to reveal a red cover, saying, “This is the revolution”.

“Everyone knew what he meant,” said Rabaté. “You had Mao’s little red book and Joyce’s big red book. Joyce’s war on the language had been successful.”

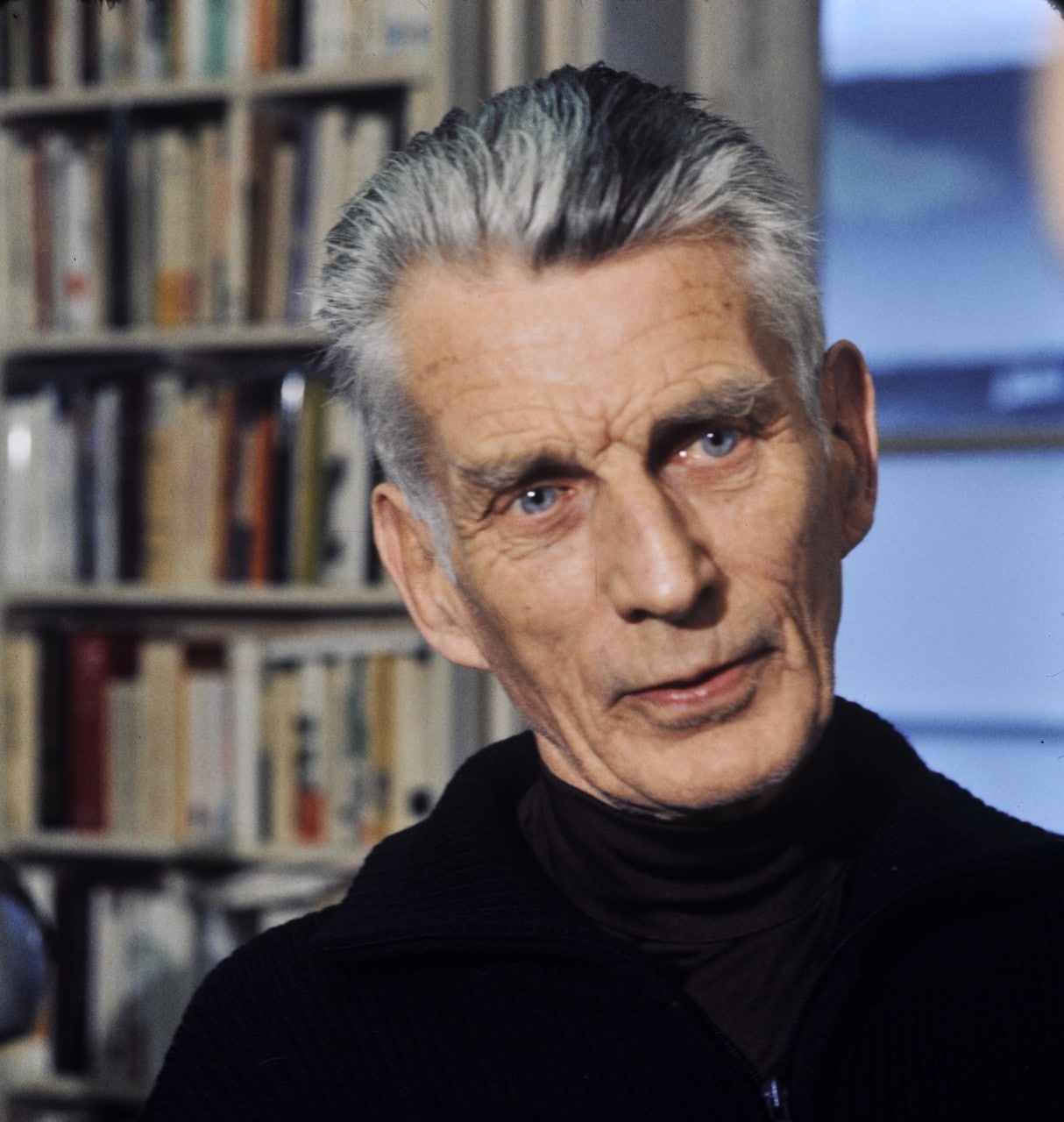

Samuel Beckett. Credit: Roger Pic

Derrida also presented Finnegans Wake as a revolutionary book in a talk he gave in 1982 at Rabaté’s invitation – “because he had created the computer of the future, an archive of the future”, anticipating technology that could store every possible combination of words. While many predicted the end of the book, instead “writing and technology have merged,” said Rabaté.

He discussed whether Joyce was also politically radical in his engagement with Italian anarchists and philosophers who “saw ‘myth’ as a political tool”. Drawing on critiques by Georges Bataille and Theodor Adorno, he said Joyce’s writing – as in Molly Bloom’s monologue in Ulysses – embraced life despite its background of war and destruction, and “saw a need for the world to wake up from the nightmare of history”.

Addressing the daunting reputation of Joyce’s writing, Rabaté said he is often invited to speak to reading groups that drink Guinness and Jameson whiskey while focusing on one page of Finnegans Wake as a language game. “I say to my students who are frightened of Finnegans Wake, Ulysses is difficult but Finnegans Wake is a game, so just play.”

SSSHARC funded Jean-Michel Rabaté’s trip to Sydney and Anthony Cordingley’s Ultimate Peer Review on December 17, 2019.