In memory of friends far away

With plans to travel from Singapore to Sydney in March for three months, “I was literally about to fly the next day when the borders closed,” she said in a Zoom interview with the Sydney Social Sciences and Humanities Advanced Research Centre (SSSHARC).

Stalla is Assistant Professor of Humanities and Associate Director of the Writing Program at Yale-NUS College in Singapore. American born and an expat most of her life, she is a scholar of modernist literature with degrees from Stanford and Oxford universities, and a creative nonfiction writer whose work is often in response to modernist writers such as Woolf.

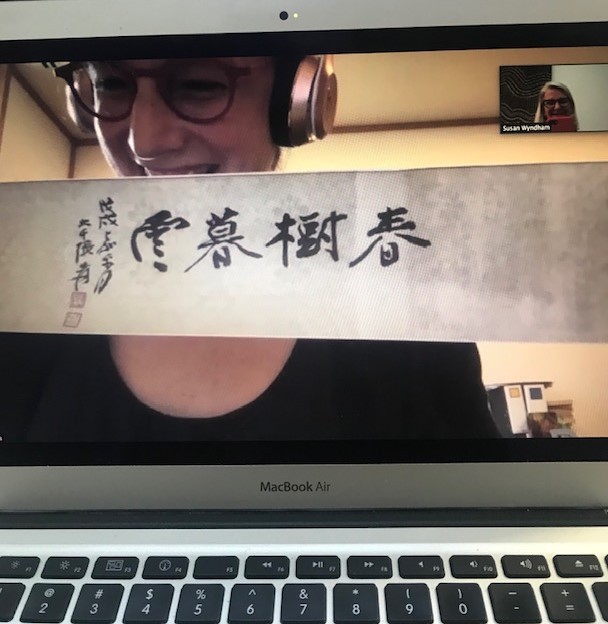

On the Zoom screen Stalla unfurled a copy of a painted Friendship Scroll – “a pandemic-perfect toilet-paper size roll,” she joked. In 1925 Ling sent the scroll with poet Xu Zhimo to England, where Bloomsbury Group artist Roger Fry and writer Dora Russell signed the parchment. By 1958 the scroll was embellished by 19 artists and writers and had travelled back and forth between London, China, Japan and Paris.

Heidi Stalla presenting a copy of a painted Friendship Scroll

The scroll represents a period of international openness and exchange in the arts. Its messages, many in classical Chinese calligraphy, are central to Stalla’s research. She had planned to study the original at Oxford University this year but that, too, was out of reach, so she had the life-size copy made and sent to Singapore.

“One goal in Sydney was to work on the scroll with people at the Chinese Studies Centre,” she said. “My challenge is that I’m a modernist, I’m interested in global modernism and I have expertise in Woolf, but I don’t know any Chinese at all.”

A pen friendship between East and West

Stalla’s Australian connection began in 2014 when she attended a conference on “Transnational Modernisms” at the University of Sydney, organised by Mark Byron, Associate Professor in the English Department. They found they shared interests in creative responses to Woolf’s work and in East-West aesthetics at the time of modernism.

She co-presented her conference paper on “Composition as Appropriation” with Dr Diana Chester, a media artist and sound studies scholar, then at New York University, Abu Dhabi. Since then Chester has joined Sydney University as Lecturer in Media Production and has worked with Stalla on a series of audio-essays.

Last year they jointly produced “Sound Puppet: A pen friendship between East and West”. This explores the correspondence between Woolf and Ling, a younger Chinese writer and artist, from 1938 until Woolf’s death in 1941. Stalla first read the letters at New York Public Library 20 years ago.

Ling wrote to Woolf from Wuhan, seeking help to write her autobiography in English. Already an admirer of the Bloomsbury Group, she had an affair with Woolf’s nephew, the poet Julian Bell, when he taught at Wuhan University before his death in the Spanish Civil War in 1937.

Virginia Woolf. Credit: Harvard Theater Collection, Houghton Library, Harvard University

Woolf and Ling did not meet but their letters discussed writing, art, grief and war; Woolf sent books and advised on Ling’s chapters. Ling later lived in London, and in 1953 published her acclaimed autobiography, Ancient Melodies, with an introduction by Vita Sackville-West.

Patricia Laurence, an American Bloomsbury scholar, found the letters from Ling to Bell and Woolf among papers auctioned by Sotheby’s in 1991 and wrote that they “introduced her as a new part of the Bloomsbury constellation of writers and artists”. Laurence examined the East-West exchange and its influence on Woolf in a 2003 book, Lily Briscoe’s Chinese Eyes. The title comes from Woolf’s 1927 novel To the Lighthouse, which describes the artist Lily Briscoe as having Chinese or Oriental eyes.

Although Woolf did not travel to Asia, she visited Constantinople. Said Stalla: “She was very interested in Eastern cultures, in archeology, in the age of exploration, in symbolism, all these things that would make her interested in China and Chinese poetry. It’s a way of thinking about human nature across time and cultures”.

Byron nominated Stalla for the SSSHARC-funded Early Career Fellowship with a collaborative project titled “Creativity in Virginia Woolf: Textual Reception and Artistic Production”. Her work in Sydney was to include teaching, workshops, and further research with Byron, Chester, and other scholars and artists.

The fellowship was also to be preparation for a larger project with a Woolf research group led by Dr Jane Goldman, Reader in English Literature at the University of Glasgow. The plan is for Glasgow scholars to come to Sydney for a symposium and an exhibition of the Friendship Scroll and related artworks at the university’s new Chau Chak Wing Museum. Byron and Stalla are also to attend similar events in Glasgow.

All this, they hope, will happen when international travel is possible and Stalla can complete her fellowship in Sydney.

Cracking the code with calligraphy lessons

Meanwhile, Stalla was in lockdown in Singapore for three months, on sabbatical from Yale-NUS, and at home with three-old twins. Like many people, she had to find different ways to work and discovered exciting new aspects to her research.

Having lost touch with a translator in China who was going to help with an English translation of the scroll, she decided to take calligraphy lessons as a start to understanding the messages.

“It was a fabulous experience,” she said, “because the course was run by a calligrapher here who happens to be interested in exchanges between East and West. So I have been able to find on the scroll that it seems like these artists are speaking across time about exchanges between East and West.

“When I was looking at it, I thought, is it going to be like passing a yearbook round a high school classroom and signing your name? But I think it’s much more interesting than that. There are conversations and responses to inscriptions that happen over 10 or 15 years, because of the length of its travel, and also that are commenting particularly on what it means to be a Chinese artist working in London and so on.”

Laborious hours spent learning to make marks with a pen on parchment also helped her appreciate the scroll as an object.

“One of my personal fascinations is how do we take an object and try and get at the things that are between the lines. There’s only so much you can get from a written correspondence between Virginia Woolf and Ling Shu Hua, but what about all the other things that don’t leave their mark through history, like sound or smell? Finding ways to embody or understand this as an artistic cultural human object, rather than just trying to find the best translator and do a literal translation, has been interesting.”

By coincidence, her calligraphy teacher owns a rare book written in Chinese by Ling, who lived in Singapore for four years. She recorded her ideas about art and conversations between East and West, and what it was like to be back in the East after living in London.

“It’s the kind of creative nonfiction writing I’m interested in and working on now, but was not so much done then – a cross between her thinking about literature and art history, and her own memoir of personal experience.”

Stalla’s father worked for an international development agency, so she moved from the US to Jordan at the age of five and every five years to Abu Dhabi, Sri Lanka, Italy and so on. She shares Ling’s sense of existing between cultures and not quite belonging anywhere.

“Spring Trees, Twilight Clouds”

As a result of all this serendipitous overlap, Stalla has decided the book she is writing will be creative as well as literary scholarship, a documentary of her efforts to understand the scroll. In conversations with other scholars, artists and translators, she has felt a “modern mirroring” of Ling and Woolf’s communication across cultures and continents, against a background of political turmoil.

In the last inscription on the scroll, written in 1958, the characters translate literally to “Spring Trees, Twilight Clouds”. Sitting beside Roger Fray’s 1925 landscape painting of trees and clouds, they seem to be a title for the completed work. An American student working with Stalla found that the phrase was a chengyu, or idiom, which appeared in classical poetry 600 years ago and means “in memory of friends far away”.

“From a creative nonfiction or literary perspective, it weaves a nice story of whimsical exchange over time,” said Stalla. “What is keeping me going with this project is that it’s important to me personally. I think what I will ultimately be exploring is an uneasiness about self and place and exchange.

“I can’t bring a knowledge of Chinese calligraphy but I can bring the impulse to send the scroll to England, the impulse to be interested in other artists and what they’re thinking about art and writing. And having that exchange over time is certainly something I can bring to it.”

As well as their shared topics, Stalla is interested in Mark Byron’s work on the modernist poet Ezra Pound. He explained to her Pound’s process of translating Chinese poetry without knowing any Chinese, and reassured her that an American woman with no Chinese can do important work on the scroll. Byron’s interest extends to later writers, such as American Gary Snyder, who have written poems about Chinese scrolls.

“Scholars like us are not necessarily expert in these Asian languages and artistic traditions,” said Byron, “but we know enough about them to understand what the modernist authors are wanting to do with that material. So collaboration is important and we need to reach out to our networks of experts in classical Chinese and Chinese art history.”

Recreating Lily Briscoe’s painting

Stalla hopes to speak at the Sydney symposium about the course she teaches on Woolf and historiography, in which students produce artworks, plays, music and other creative responses to Woolf’s work. One student staged the party from Mrs Dalloway, and another painted Lily Briscoe’s painting from To the Lighthouse as if the artist were a young woman living in Singapore today.

Virginia Woolf, Mrs. Dalloway (1925) Dust jacket designed by Vanessa Bell

“My theory is that this kind of work, like taking the calligraphy class to understand the scroll, allows deeper ways of thinking about the text by embodying a creative process that’s not just an academic essay. You have to stop and really think and have an adherence to the relationship between form and content that you don’t if you’re just reading for a literature class.

“I ask them after they do this work to talk about Woolf and I find there is an excitement and an understanding that is so much more profound after they’ve gone through this process.”

Byron expects their presentations will attract students in the English Department, including native Chinese speakers, all interested in the visual arts and trained in Western literary scholarship. There will also be an opportunity for cross-departmental conversations with people in Chinese Studies, Japanese Studies, Art History, and other subjects.

The work Byron and Stalla are doing on East-West transmission of knowledge is a form of cultural exchange that echoes the original. “It is a useful way of bringing people together to communicate, a fantastic gesture, and the exhibition would be housed in a gallery funded by a major Chinese-Australian philanthropist,” he said.