Desecration and romanticisation – the real curse of mummies

Hollywood's tomb of old ideas will creak open again and present the tale of an ancient Egyptian tomb with the latest installment of The Mummy. Dr Craig Barker from Sydney University Museums sorts the fact from fiction.

This June Hollywood’s tomb of old ideas will creak open yet again and present the tale of an ancient Egyptian tomb disturbed by a bumbling archaeologist and/or action-adventure hero, who inadvertently and unwittingly unleashes a curse.

This curse will resurrect a mummy seeking either vengeance or a lost lover, wreaking havoc on contemporary society until our hero can stop it. This year The Mummy, directed by Alex Kurtzman, will see Hollywood pharaohs Tom Cruise and Russell Crowe face off against a female mummy played by Sofia Boutella.

Heard it before? Kurtzman’s film is just the latest in a staggering line of mummy-mania and Egyptophilia predating even the discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb in 1922.

While popular culture has delighted in mummies for over two centuries, in that same time real Egyptian antiquities have been looted, lusted after, and desecrated. In the 19th century, it was even fashionable to host “unwrapping” parties, where mummies were revealed and dissected as a social event within Victorian parlours.

What is mummy studies?

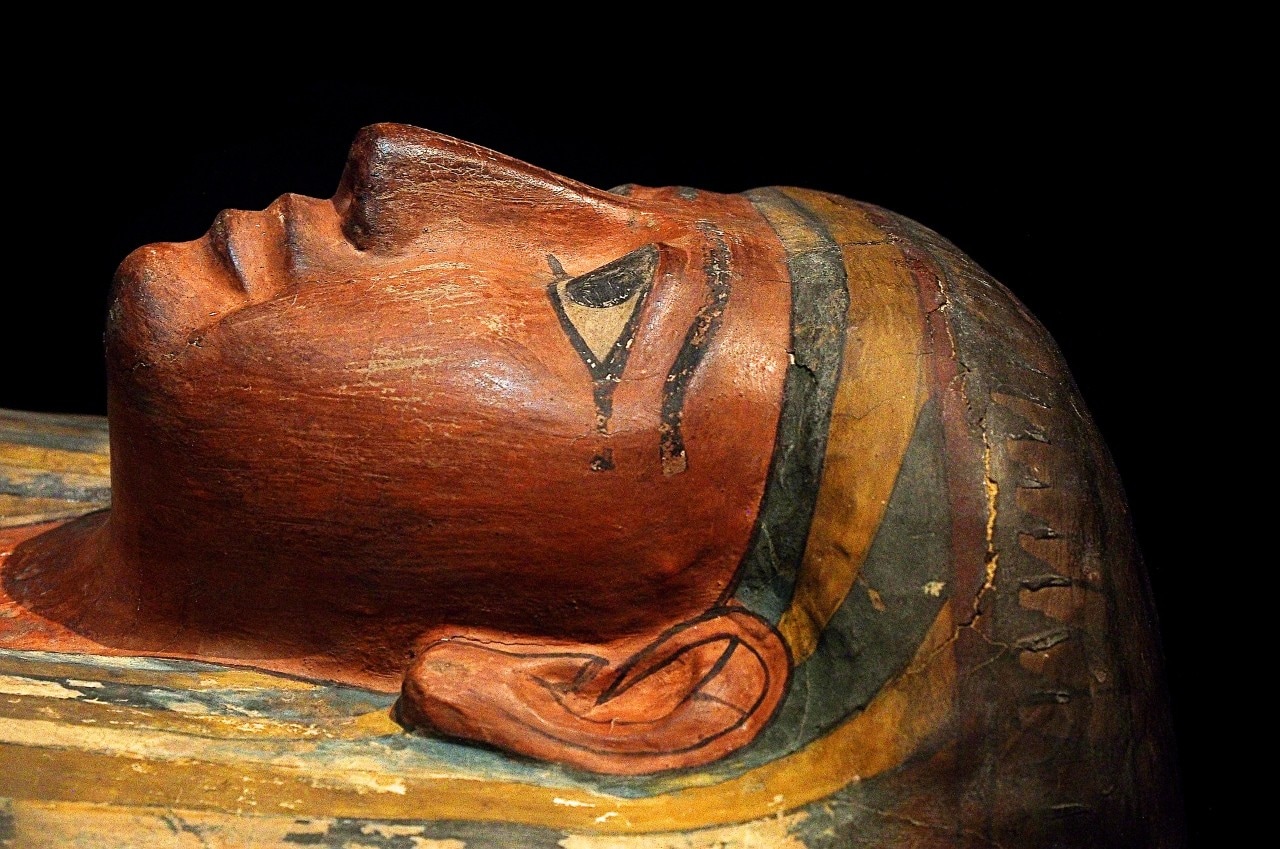

A mummy is a deceased human or animal whose skin and organs have been preserved. This can either be done deliberately, through chemical embalming processes, or accidentally, thanks to the climate. A number of ancient cultures practised deliberate mummification, such as the Chinchorro people of South America, and most famously, the desiccated bodies of ancient Egypt, which were meticulously prepared for the afterlife.

Mummy studies has become a major academic discipline and more continue to be found. Within the last month we have seen the discovery of 17 mummies in a necropolis near the Nile Valley city of Minya and the finding of a New Kingdom nobleman’s tomb in Luxor. Despite this level of scholarly attention and meticulous archaeological investigation, sadly illicit looting and smuggling of antiquities from Egypt, including mummies, continues today.

Everything really old is new again

With a reported budget of $125 million, filmed principally in Oxford and the British Museum, The Mummy is a big budget investment for Universal Studios. History suggests that the movie will be a major success.

Still, the mother of all mummy movies remains the 1932 original Universal film The Mummy, starring Boris Karloff; it sets the template for the others to follow. Egyptian priest Imhotep, sympathetically played by Karloff, was mummified alive for attempting to revive his forbidden lover, the princess Ankh-es-en-amon.

Discovered by archaeologists who resurrect him by reading from the Scroll of Thoth, Imhotep believes that a modern woman Helen Grosvenor (played by Zita Johann) is the princess’ reincarnation and hunts her through modern London. Not so much a monster then as a misunderstood lover.

More than a dozen films followed, from the 40s-era (The Mummy’s Tomb), the 50s (The Mummy) the 80s (The Awakening), and culminating with the 1999’s box office smash, The Mummy, which spawned two sequels and a spinoff prequel franchise.

Each of these films has fundamentally the same plot. In the 2017 version, a woman is raised from the dead rather than a man, but even this is not new. Hammer’s Blood From the Mummy’s Tomb (1971) featured a female mummy (Valerie Leon), who is revived and then walks around in far-too-few clothes for a London winter.

Of curses and kings

Why is the mummy such a popular trope in horror cinema? The mummy, it can be argued, symbolises some of our most basic fears surrounding mortality. The mummy’s enduring appeal can also be traced to the one archaeological dig everyone on the planet has heard of: Tutankhamun’s tomb.

The discovery of this tomb by Howard Carter in the Valley of the Kings in 1922 made international headlines. The resulting Tut-mania influenced all manner of popular culture from Art Deco design and fashion, to pop songs and advertising.

A recent exhibition at Oxford’s Ashmolean Museum explored just how famous Tutankhamun was during this key period of mummy-mania. Media coverage of the excavations was insatiable. Carter had an exclusive deal with the Daily Express newspaper, which led other reporters to embellish their stories.

While Tutankhamun perpetuated the Hollywood craze for mummies, the public fascination for curses predates Carnarvon’s unfortunate death.

This led to reports of a supposed (but non-existent) curse on the tomb, “Death comes on swift wings to him who disturbs the peace of the King”. It was nonsense of course, but once the financier of the archaeological project, Lord Carnarvon, died in Cairo thanks to an infected mosquito bite, the curse story took off faster than any real news. In popular culture, mummies and curses became irreversibly linked.

The discovery of Tutankhamun by Carter’s team has itself inspired a number of fictionalised retellings, of varying degrees of fidelity to history, including the movie The Curse of King Tut’s Tomb (1980), a TV movie remake of the same name in 2006, and the 2016 British TV series Tutankhamun.

While Tut perpetuated the Hollywood craze for mummies, the public fascination for curses predates Carnarvon’s unfortunate death. A series of silent films with mummy themes were made in the first years of cinema, including Cleopatra’s Tomb (1899) by pioneering film-maker George Melies, and 1911’s The Mummy. Unfortunately most of these have not survived.

There was also a rich 19th-century tradition of mummy literature. Mummies appeared in everything from serious works to penny dreadfuls. A number of famed writers told stories that cemented the curse story, including Louisa May Alcott’s Lost in a Pyramid: or the Mummy’s Curse (1869); Bram Stoker’s Jewel of Seven Stars (1903) and Arthur Conan Doyle’s Lot No. 249 (1892).

Other works went beyond curses. Edgar Allan Poe’s Some Words With a Mummy (1845) was a satirical comment on Egyptomania. There were also romance novels, perhaps best typified by the 1840 story The Mummy’s Foot by Théophile Gautier, in which a young man buys a mummified foot from a Parisian antiques shop to use as a paperweight. That night he dreams of the beautiful princess the foot belonged too, and the two fall in love only to be separated by time.

A number of scholars, notably Jasmine Day, have been investigating the role of mummies in 19th-century fiction, and one interesting aspect is the number of female writers of these tales.

One of, if not the earliest, mummy story, was Jane Webb (Loudon)’s The Mummy!: Or a Tale of the Twenty Second Century (1827), which charts the revival of Cheops in the year 2126. Other female writers provided an interesting subtext and perspective.

This article was written by Dr Craig Barker, Manager of Education and Public Programs at Sydney University Museums.

It is based on a longer article that was originally published on The Conversation. Read the full article here.