Making deer fair game for unlicensed hunting in NSW

Deer are already considered a pest. Last year the NSW government approved 11 regional pest animal plans, each of which declared deer as a priority pest species. Several hunting regulations have already been suspended to manage abundant deer populations, and in February 2019 the government announced a A$9 million deer control program described as the most extensive of its kind.

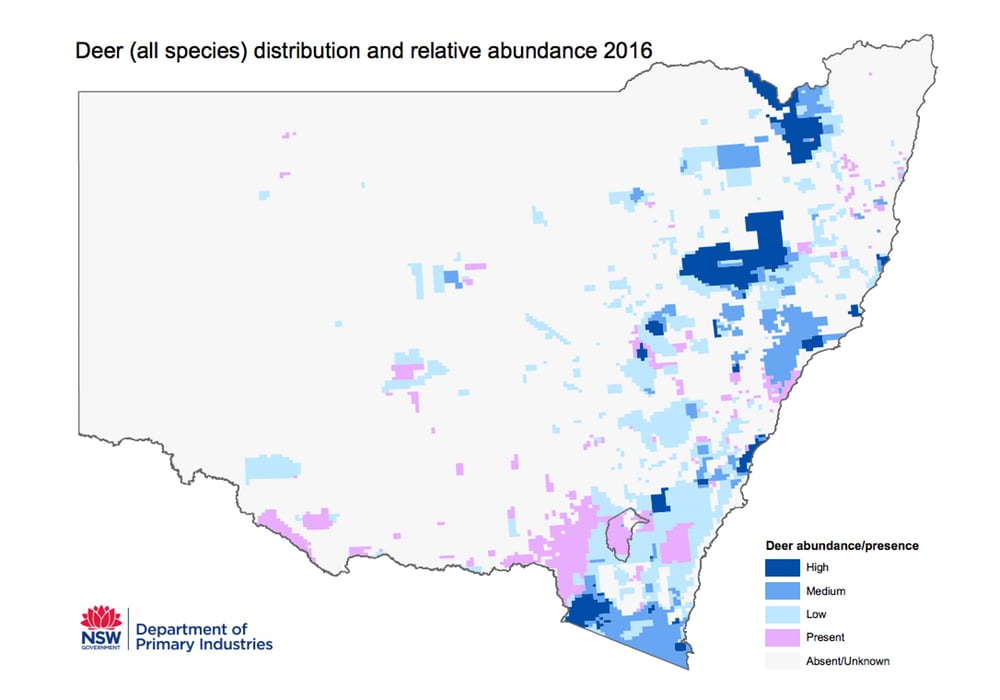

Removing the game status of deer is the next logical step towards controlling existing deer numbers in NSW, and slowing their spread to new areas. Deer currently cover 17% of NSW, and this area has more than doubled since 2009. Without urgent and effective control, the deer population could spread throughout the entire state and beyond.

If the plans go ahead, deer will no longer be afforded protection under the state’s animal control laws. This will mean that a game hunting licence would not be required for recreational, commercial and professional hunting of deer species. Restrictions on how and when deer can be hunted would also be lifted.

Feral deer will be treated the same as other pest animals in NSW, including red foxes, feral cats and rabbits.

The impacts of deer

Feral deer remain one of Australia’s least studied introduced mammals. Yet the evidence shows they have a substantial impact on Australia’s ecosystems and agriculture.

Since 2005, grazing and environmental damage by feral deer has been listed as a key threatening process under NSW legislation. Deer are known to graze on threatened plant species, and also cause erosion and soil compaction. They damage pasture; destroy fences and contaminate water sources; harm trees via antler rubbing; rip up the ground during rutting season; and potentially contribute to the spread of livestock diseases.

Deer are a threat to humans too. The Illawarra region south of Sydney, a hotspot for deer activity, has seen one death and multiple serious injuries between 2003 and 2017 due to vehicle collisions with deer.

Deer can also carry pathogens that cause human disease such as Leptospirosis and Cryptosporidium.

Effective control is needed to stop the spread of feral deer in Australia.

Photo: Emma Spencer

Choosing the right control method

Ground-based shooting is the main way to manage deer in the urban fringes, regional areas and national parks. Unfortunately, coordinated ground shoots have only been effective for areas of less than 1,000 hectares, and there is no evidence that uncoordinated shooting by recreational hunters actually works to control deer on a widespread basis.

Aerial shooting can potentially be more successful over large tracts of land, but may not be a good option when tree cover is high and visibility is low. Poison baiting could help, although there is no method available to deliver baits safely, effectively and specifically to deer.

Irrespective of the control method, a coordinated approach is needed. We need a strategy that not only controls deer where damage is worst, but also prevents their spread to new areas. This will require NSW to work closely with the ACT and Victoria.

A red fox feeds on a culled feral deer. Photo: Emma Spencer

Rigorous monitoring will also be vital. This is important to gauge success (how many deer were culled, and the ethics of shooting, trapping and baiting), and to determine whether the control efforts have unintended impacts on the environment, such as deer carcasses providing food for scavenging pests.

Scavenging pests have been observed feeding on carcasses, but whether culling deer and other feral animals actually increases their abundance and impacts is unknown. Carcasses also provide a source of food for native scavengers such as eagles and ravens, and are integral to the structure and function of ecosystems.

The negative and positive impacts of deer culling on the broader ecosystem therefore needs consideration when developing and implementing monitoring plans. NSW can be the leader in this regard, starting from day one after removing the status of the deer as a game species.

This article first appeared in The Conversation, written by Dr Thomas Newsome and PhD candidate Emma Spencer, of University of Sydney and co-authors.