Nip and tuck

Some conservation treatments for cultural objects made of skin (a pair of leather shoes or the velum page of a book), can be applied to the conservation of specimens, but there are some quite strange things about taxidermy which require specialised methods to preserve the skin on animal specimens.

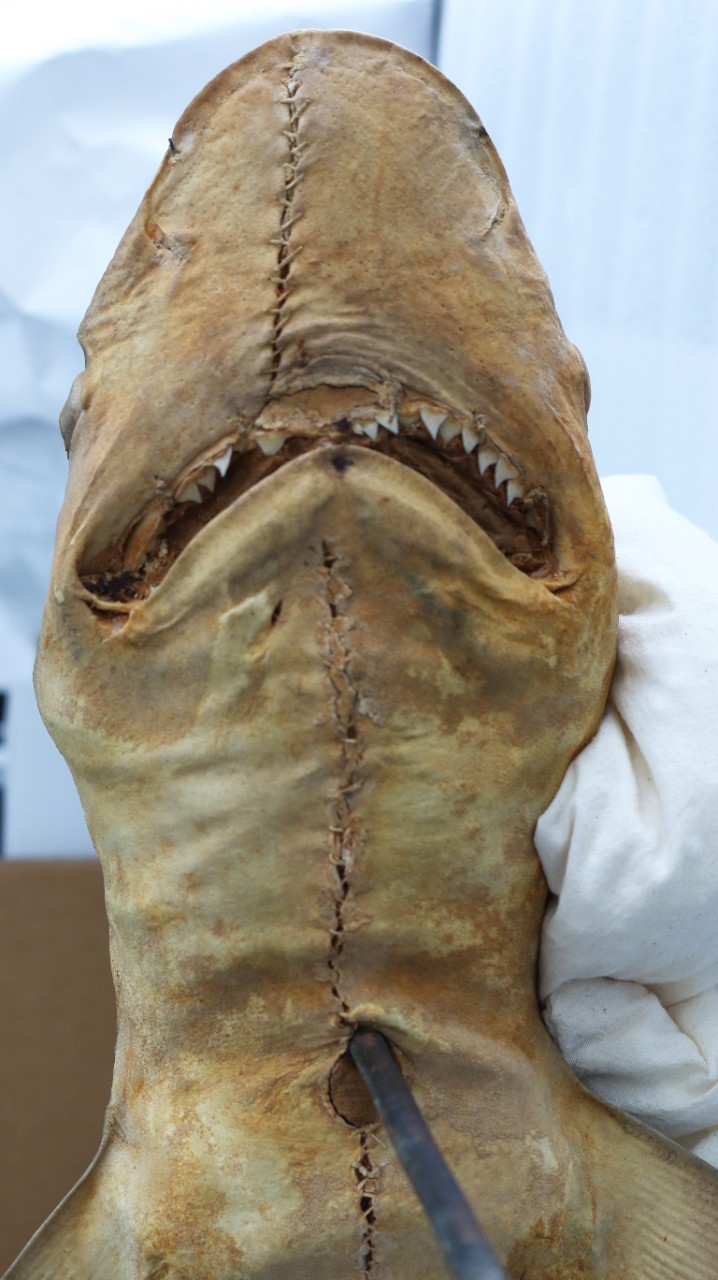

Sasha Stollman works on a shortfin mako shark.

In preparing Natural Selections, our major natural history exhibition for the opening of the Chau Chak Wing Museum, we were able to again work with conservator Sasha Stollman. Along with mammals needing her expertise, Sasha spent a lot of time with large fish, in particular sharks. In her treatments, she had to take into account the thin layer of stretched and painted skin and the brittle and vulnerable fins, as well as the multitude of materials used by 19th century taxidermists: sawdust, cotton wool, paint, varnish, thread, pins, iron struts, wooden blocks, preservation chemicals and glass.

One mako shark has become more akin to a goofy animated version of itself than the intended representation of the animal ‘in life’.

Mostly, when I picture a conservator at work, I think of a person bent over patiently inspecting something with specialist magnifier glasses and a small instrument in hand. But, in reality there’s also talking over problems, investigating the literature, and detailed report writing, such as this description of a dusky shark, Carcharhinus obscurus, taken from Port Jackson in the 1870s:

Taxidermy dusky shark skin over steel armature (not x-rayed). Two steel mount pins attached internally to armature protrude through underside incision. Mouth stitched partially shut through centre of upper and lower lips; upper teeth exposed; mouth interior coated with a putty. Vegetable fibre stitching secures incision running along underside from tip of nose to start of tail and up [right] side of tail. Specimen stuffed with a coarse sawdust, red ochre in colour. Some portions of gap along underside seam have been filled with an ochre coloured putty during original preparation or later as skin dried and seam opened. Good eye on [left] side is painted on. Presence of pesticides not tested.

Sasha Stollman in the final stages of realigning the kingfish fins.

Sasha’s description charts some of the taxidermist’s work, such as stitching and stuffing, and the decisions made to show aspects of the specimen, such as teeth. Macleay’s taxidermist Edward Spalding could not have foreseen the kind of skin shrinkage and movement caused by changing humidity over the next 140 years: one mako shark (pictured top of page) has become more akin to a goofy animated version of itself than the intended representation of the animal ‘in life’. Dr Tony Gill, Curator, Natural History, has suggested the shrinkage causing the fins to bend may have been because the substrate is fin cartilage, which over time has dried and shrunk at a different rate to the skin. This, in conjunction with poor storage, ‘animated’ the shark.

Holding together, but only just

Countering this damage involved some plastic, pegs, vaporised water, great care, skill and time. After initial cleaning and checks for splits in the skin, Sasha slowly humidified the affected area (enclosing the section within a bag), gently weighted sections with clamps, and then waited. When needed, additional strength was provided by Japanese paper backing, held in place with ethyl cellulose. Thanks to these methods, the fins are now straighter, and the tails and gills are less precarious.

Skin shrinkage also caused stitches in the dusky shark specimen to move apart, allowing sawdust to leak out. Japanese paper could have been used here, but as our initial project had shown, taxidermy details are vital to historical research on the collections. So, when closing up gaps between the stitches, Sasha used transparent ‘gold-beaters skin’ (made of intestine) so the stitching can still be seen through the repair. Thus some shark specimens now have calf intestine membrane on top of their own skin, held in place with a transparent adhesive.

Pteropus tonganus, Pacific fruit bat, Macleay Collections, NHM.226.

One very old bat

Nothing in the collection demonstrates better the conservator’s patience in transforming a damaged specimen than the work on the Tongan fruit bat, Pteropus tonganus, which had many splits caused by age and handling. Aside from specialist mammal problems (ears are particularly vulnerable and often require reshaping), the process was similar to the shark treatments: gentle surface cleaning, humidifying to ‘relax’ specific areas, and split repair.

Sasha Stollman works on the membrane of a bat wing.

But, on which side of the translucent membrane of skin between each ‘finger’ of the bat wing should the repairs be made? Investigation was needed to understand how this bat – which has no stand or wire – was originally displayed. The position of the wings and legs would allow for the specific taxonomic details of its sex, colouring and anatomy to be apparent. Some tiny holes in the skin indicate possible exhibition pinning spots to fix the bat to the back of a case; the position of the eyes also suggests this.

Once the decision was made, the top surface of the wing was chosen for the reversible repairs. This treatment took more than two weeks of humidifying and gentle straightening, followed by more localised humidification and realignment. Lastly, the final alignment and reversible sticking of specially ‘bat-wing’ tinted paper could be applied.

It is incredibly exciting to see these historic specimens cleaned up and straightened out, ready for their first public appearance in many years. This September, these large, heavy animals have moved from their old home to the new museum ready for conservators Gemma Tora Campos and Madeleine Snedden to do final checks, while specialist museum technician Kevin Bray designs and constructs mounts to hold them securely in place for exhibition in Natural Selections.

Written by Dr Jude Philp, Senior Curator, Macleay Collections.

With thanks to Sasha Stollman.

A version of this article was originally published in Issue 22 of Muse Magazine, 2019.

Top image: Isurus oxyrinchus, mako shark, Macleay Collections, NHF.1669.