Getting to the guts of Tasmanian devil health

Picture a cold June morning in Tasmania. It’s 5.30am and Rowena Chong is heading out to start a day of field work on Marie island, home to approximately 100 Tasmanian devils. She is there to collect samples of their poo.

Tasmanian devils have been at risk of extinction due to a fatal contagious cancer, devil facial tumour disease. Research on this cancer has been extensive, but little is known about other health challenges in devils, and studying them could improve conservation of this endangered species.

This is where Rowena’s research comes in.

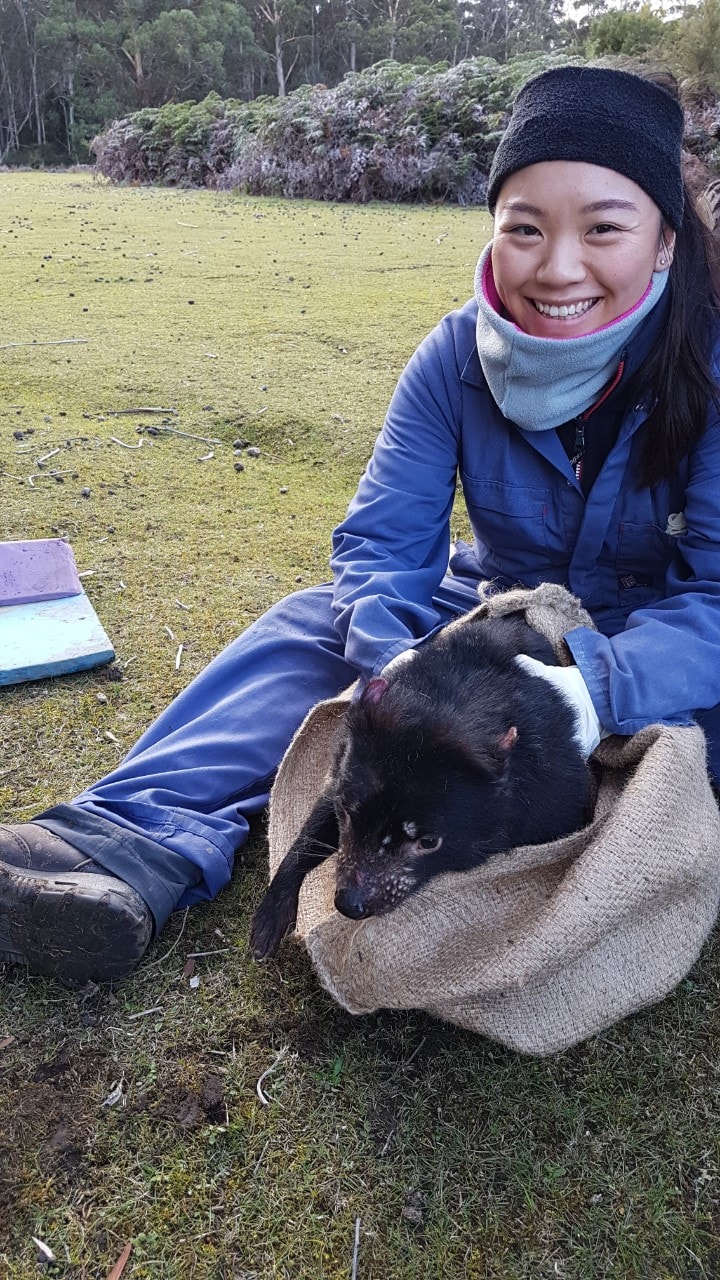

Rowena got to work hands on with the animals she had been researching.

What sparked your interest in Tasmanian Devils?

I have always been passionate about wildlife and wildlife conservation. I remember seeing a Tasmanian devil at the zoo for the first time and learning about the devil facial tumour disease. I was fascinated by this strange disease and wanted to find out more about how we could save them from extinction. During my animal bioscience degree, I got to learn about some of the research that was being conducted on Tasmanian devils by Professor Kathy Belov, who is now my research supervisor. I have since learned so much more about this unique Australian species!

A messy job - cleaning the Tassie devil traps.

Why did you focus your research on the devil’s gut flora?

We now know that our gut flora, or gut microbiome, plays an important role in shaping our health - from nutrition to immunity, and even the way we behave. Microbiome research in wildlife species is still in its early stages but has the potential to improve conservation of threatened species.

The Tasmanian devil gut microbiome was first investigated in 2015 by our research group, which found that devils living in captivity had very different microbiome compared to those in the wild. Imbalances or alterations to the microbiome could have negative impacts on host health, and even host survival when captive animals are reintroduced to the wild. Understanding these microbiome changes can help improve the way zoo animals are managed to ensure optimal host health and wellbeing, especially when they are returned to the wild.

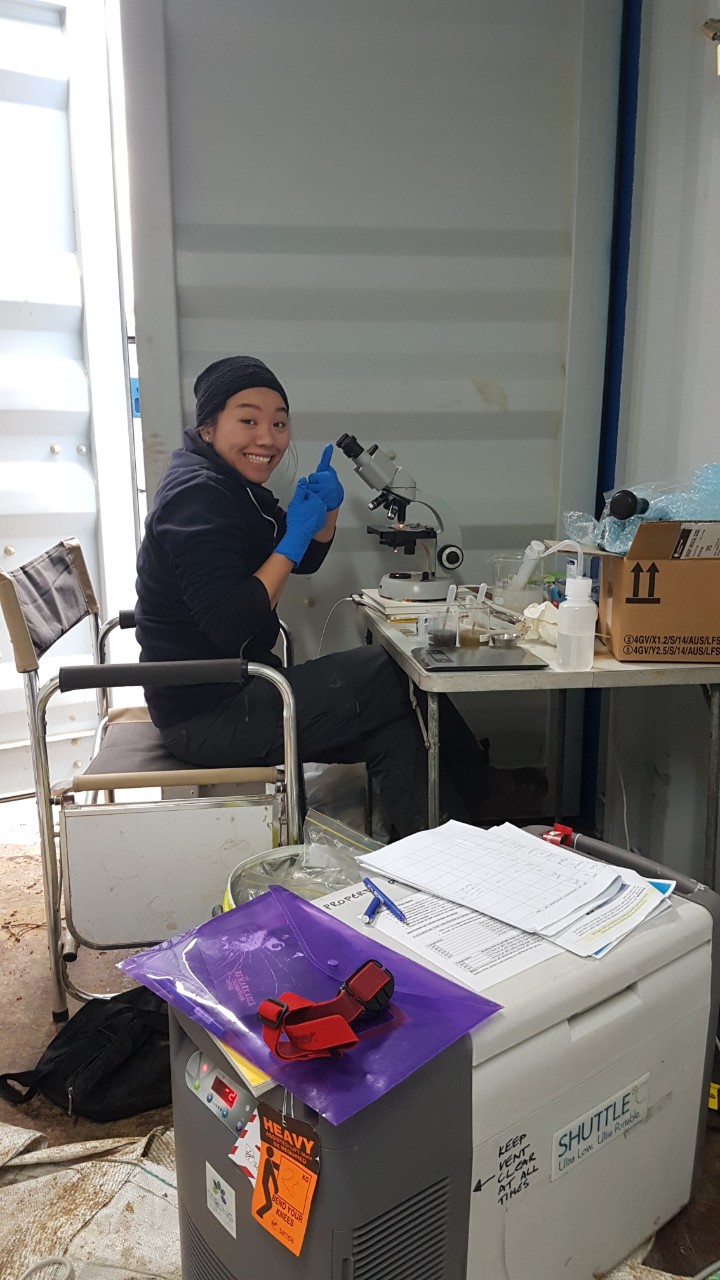

The reality of field work. Sometimes Rowena would process samples in a cold shipping container, other times in a nice Airbnb!

What has been the most interesting part of your research?

It would definitely be the field work. My field work took me to some of the most beautiful places in Tasmania and gave me the opportunity to see and work with the animals I had been researching.

A typical day of field work starts with waking up early in the morning and checking all the devil traps that were set up the night before. Once trapped, the devils get a health check and their samples collected. We also spend a lot of time cleaning the traps, which is important for preventing the spread of disease. Trapping typically finishes just before dusk, when I would start processing all my samples, which includes spending hours counting parasite eggs in poo samples. Depending on the field site, I have done this inside a shipping container or a nice Airbnb in front of the fire with ocean views!

What do you hope to achieve with your research?

I want to learn more about the gut flora of the Tasmanian devils and the different health challenges they might face besides the Devil facial tumour disease. I hope that my research will contribute to improving their overall health, so that they will continue to thrive in the wild. I also hope to raise public awareness about our native wildlife through science communication and outreach.