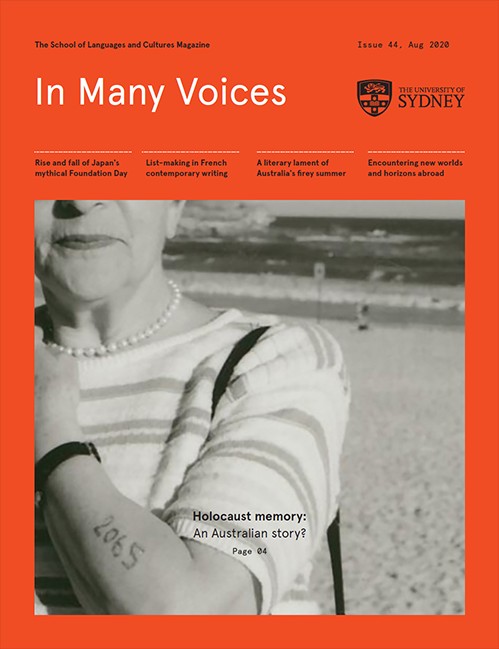

Holocaust memory: An Australian story?

On 9 and 10 November 1938, the state-sponsored pogrom, which came to be known as Kristallnacht (Night of Broken Glass), was enacted against the Jews of Germany and Austria.

Less than a month later in Australia, an Aboriginal Elder of the Yorta Yorta nation William Cooper, the driving force behind the Australian Aborigines’ League, led a delegation to the German consulate in Melbourne to protest these events. Although refused entry, his petition “on behalf of the Aborigines of Australia, was a strong opposition against the cruel persecution of the Jewish people by the Nazi government of Germany”. This was made public that same day, but sadly attracted little attention.

Cooper’s stand is one of the first links between Australia and the Holocaust which may, initially, seem less than self-evident.

When we think about Australia’s participation in World War II, it is the war in the Pacific that more frequently springs to mind. Visions of the prisoner-of-war camps crowd our individual and national memories, rather than the concentration camps of Nazi-occupied Europe.

Yet, in the immediate post-war period, it was Australia that became home to the largest per capita number of Holocaust survivors – second to the newly formed State of Israel – despite continued quotas on Jewish migration that went beyond the overall restrictions imposed by the White Australia policy.

Jewish survivors on board the Cyrenia en route to Australia, 1949. Photographer unknown.

Australia’s then-substantially enlarged and culturally transformed Jewish community created principally survivor-led commemorative rituals, as well as institutional repositories of Holocaust memory.

While always in flux, these manifestations of memory were mainly inward-looking and particularistic, a perspective that has slowly altered as generational change has shifted communal outlooks and priorities. We see such transformations in the Sydney Jewish Museum. In the past decade, we have begun to observe more outward-facing exhibitions and educational initiatives.

The Holocaust and Human Rights exhibition. Sydney Jewish Museum, Australia. Curated by Dr Avril Alba, Professor Jennifer Barrett and Professor Dirk Moses in 2018.

In the broader Australian community, Holocaust memory has also been influential. But, by contrast, it has largely been directed toward more universal issues and experiences. Post-war quotas placed on Jewish migrants both before and after the war have been consistently referenced to highlight the discriminatory nature of Australia’s immigration policies of the 1970s. The Holocaust was, again, deemed a matter of national import as evidence came to light that war criminals were knowingly allowed entry into Australia as part of post-war resettlement schemes for displaced persons.

Australians debated on whether justice would be served through undertaking war crimes trials in a land so far removed from Nazi crimes. From its appropriateness as a comparative tool in Australia’s “History Wars” to reflection upon the genocidal implications of the Stolen Generations report, the analogical and generative power of Holocaust memory has been continually brought to bear in some of Australia’s most important – and divisive – national debates.

As we witness the imminent passing of the survivor generation, there is an urgency to account for diverse uses of Holocaust memory in the Australian setting.

Interrogating the uses of this memory provides a bridge between the generation of living memory and those who come after. This is achieved by documenting and analysing the shape and impact of Holocaust memory at this key point of transition.

Indeed, in exploring the various uses of this memory in Australia, many questions arise: With an imperial history of racial exploitation, what are the tensions that emerge in a postcolonial Australia when confronting the enormity of Nazi crimes? How was memory of the “Final Solution” reconciled with the continuation of the “White Australia” policy and Australia’s later transformation to a “multicultural” nation?

To what extent was – and is – the Holocaust present in post-war and contemporary public debates about decolonisation and reconciliation? How does it affect the articulation of racist and anti-racist politics?

How did the Holocaust change perceptions of Jewish people in Australia, and other “racialised” groups who responded to the legacy of Nazism in light of their own histories of suffering and exclusion?

From Cooper to the present, these questions remain relevant and pressing.

Ultimately, harnessing this powerful memory has the potential for a reconsideration of Australia’s own history of race and racial oppression. As the memory of the Holocaust on Australian shores is increasingly laid bare, so too will its enduring impact be more fully appreciated.

Dr Avril Alba is Senior Lecturer in Holocaust Studies and Jewish Civilisation in the Department of Hebrew, Biblical and Jewish Studies. Supported by the Australian Research Council, her ARC Discovery Project, The Memory of the Holocaust in Australia, will produce the first cultural history of Holocaust memory in the Australian context.

This article is adapted from the School of Languages and Cultures’ magazine In Many Voices (August 2020, Issue 44). Read Dr Avril Alba’s full feature article on our digital online reader.