The EJ Series, part 13: settlers, miners, same thing.

By Dr Seán Kerins, the Australian National University

This article is based on a presentation by Seán Kerins, on a panel entitled ‘Instruments of Injustice’ at the Environmental Justice 2017: Looking Back, Looking Forward Conference, the University of Sydney, 6-8 November 2017.

Jacky Green, a Garrwa artist and cultural warrior, and Patrick Wolfe, the late Australian historian, remind us through both art and academic literature, that the settler-colonial logic of eliminating native societies to gain unrestricted access to their territories is not a phenomenon confined to the distant past, but rather, an ongoing structural process.

It is this ongoing structural process that I want to talk about today and briefly trace its history alongside the Australian narrative of ‘developing the north’.

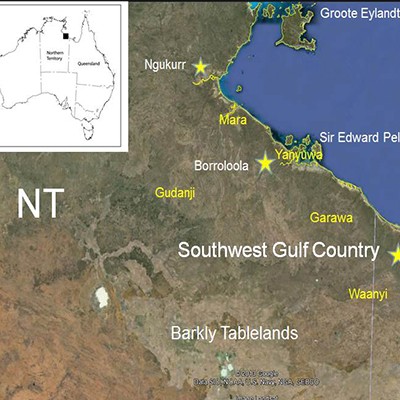

I want to locate my talk today in the southwest Gulf of Carpentaria region of the Northern Territory of Australia in the territories of the Garawa, Gudanji, Marra and Yanyuwa peoples.

Indigenous peoples of the southwest Gulf Country.

The conflict between settler society and Indigenous peoples over access to and control of natural resources in the southwest Gulf country has been occurring since Europeans first invaded the ancestral lands of the Garawa, Gudanji, Mara and Yanyuwa peoples.

The conflict began in the 1870s with the rise of the pastoral industry and the contest over land and water resources for livestock production. Within a few short years the entire Gulf region had been leased to just 14 landholders, all but two of whom were wealthy businessmen and investors from the eastern colonies.

With the long dry season many of the region’s rivers, streams, creeks and wetlands were taken over by the cattle. These places were at the heart of Indigenous economic activity. Essential Indigenous food resources, along with important cultural sites, were damaged by thousands of cattle.

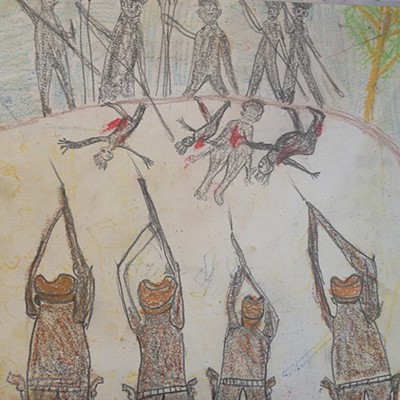

With food swiftly disappearing and some waters fouled by the cattle and the rotting carcasses of bogged animals. Groups of Indigenous people mobilised to resist the destructive aspects of capitalism that sought to eradicate their livelihoods and the associated complex web of ecological and cultural systems. The response from the settlers was one of violence, murder and intimidation.

Drawing of settler colonial violence in the Gulf Country, Dinny McDinny (1927-2003).

In the 1950s another conflict over land and natural resources began when Mt Isa Mines Limited (MIM) was granted mining leases by the Australian Government for zinc-lead-silver deposits.

They were located in Gudanji country adjacent to, and under, McArthur River about 70 kms southwest of Borroloola. Due to a number of technology limitations and doubts about profitability the ore remained virtually untouched, until the early 1990s.

Throughout this time relations between the region’s Indigenous peoples and MIM was complex with Indigenous peoples seeking to both defend their country and accommodate mining development.

Between 1974 and 1977 it was recorded that there were 36 Aboriginal camps within or contiguous to McArthur River catchment. Some camps were permanently occupied, with others occupied for shorter periods of time. A significant amount of food resources were obtained from this region, especially important was the area at Bing Bong for turtle and dugong hunting camps.

In 1977, to defend their country, the Yanyuwa people lodged the Borroloola Land Claim, the first under the ALRA 1976. The claim included large areas of the McArthur catchment around Borroloola (the Town Common), as well as the Sir Edward Pellew Group of Islands. MIM opposed the land claim even though the mine site was not situated within the boundaries of the land claim. The land claim resulted in only partial success for the Yanyuwa people.

In 1978, the Aboriginal Land Commissioner, Justice Toohey, recommended the grant of the Borroloola Town Common and only two of the five major islands of the Sir Edward Pellew Group (West and Vanderlin Island). Toohey withheld recommending the grant of the middle group of islands (North, Centre and Southwest), citing a lack of ‘traditional attachment’.

Toohey also excluded a one kilometre wide land corridor from the Borroloola Town Common for a future road, railway and pipeline from the proposed mine site to an imagined deep sea port on Centre Island.

Soon after the land claim the NT Government proclaimed the ‘Township of Pellew’ over both Southwest Island and Centre Island and declared a conservation reserve over North Island in the hope of putting the land permanently out of reach of the land claim process.

Borroloola Land Claim map 1978

Not to be defeated, Gudanji and Yanyuwa people sought to acquire three pastoral leases—Bing Bong, McArthur River and Tawallah—that together comprised a significant part of their ancestral lands. They did not succeed with the purchase through the Aboriginal Land Commission Fund. They were trumped in last minute negotiations by MIM who out bid them, greatly expanding their influence in the McArthur River region from a mining reserve of 693 square kilometres to almost 6000 square kilometres through the purchase of the three leases and amalgamating them into one large lease known as McArthur River station.

The struggle over large scale development in the Gulf country shouldn’t be seen as a two-sided conflict between economics and ecology, but one that has another important dimension of conflict, namely the cultural.

Anthropologist Arturo Escobar argues that these conflicts arise from ‘relative power, or powerlessness accorded to various knowledges and cultural practices’.

The Land Commissioner’s decision to excise areas from the land claim can be seen as culturally privileging the capitalist [e.g., pastoral and mining] model of nature over local diverse Indigenous livelihoods and their ecosystem services not geared to a single product and to accumulating capital. And, in doing so creating not only a resource distribution conflict but also a cultural conflict.

At the heart of cultural conflicts are reflections of ontological difference. That is different ways of seeing, experiencing and understanding the world.

Indigenous peoples in the Gulf imbue the environment with ‘meaning-making practices that define the terms and values that regulate social life concerning economy, ecology, personhood, body, knowledge, and property’.

While these nature—human relationships are at the centre of Aboriginal custom throughout the Gulf region with their protection and maintenance vital to Indigenous wellbeing and their survival as distinct groups of Indigenous peoples, such relationships are not valued and are rarely seen in large scale development projects.

Indigenous cultural meanings and practices are rendered meaningless by settler colonisers, they become ‘externalities’ placed outside the market where they are made invisible.

Over the past decade across the Gulf region there has been a massive increase in the mining and energy resource extraction developments with few benefits flowing to Indigenous peoples, while it is they who bear the costs.

Aboriginal people are alarmed at the increased environmental destruction and pollution they are witnessing.

They are alarmed that species they once hunted, fished and gathered are quickly disappearing and that many of their important fishing and hunting places are now off limits, because of access restrictions or pollution.

“Bing Bong used to be a place our families went camping, hunting and fishing. Miriam Charlie (Garrwa/Yanyuwa). Photo Miriam Charlie.

They are increasingly alarmed that they can’t make their voice heard in the development debate. And, they are also alarmed that their long-term life-project of living on and caring for country, which is ‘embedded in local histories and encompassing visions of the world and the future that are distinct from those embodied by projects promoted by the state and markets’, is being snuffed out.

All large scale developments in the Gulf have left legacy issues for Indigenous people. Almost inevitably, affected Indigenous communities eventually pay in posterity for the degradation or repair of market ‘externalities’.

Redbank copper mine, was left in the mid-1990’s with an estimated 54,000 tonnes of partially treated and acid forming material on site. The massive stockpile was left exposed to the monsoonal rains for 17 years, resulting in highly toxic water extending up to 7 kms from the mine site. The copper sulphide leaching forms concentrations so high in some waterways that there is no longer aquatic life.

Copper sulphide from Redbank mine flows directly into Hanrahan’s Creek killing all aquatic life, Photo Jessie Boylan.

McArthur River Mine, owned by international mining giant Glencore, poses the most serious and long-term legacy issue for Gulf people. Here, levels of lead found in the fish in the mine’s diversion channel exceed the maximum permitted by Food Standards Australia New Zealand. In 2013, the permitted lead level was exceeded in 9 out of 10 fish caught. The lead tested similar to that found at the mine site.

The massive waste rock pile, now a permanent feature of the landscape, contains around 80% of the waste rock thought to be potentially acid-forming material. Overtime, monsoonal rains will penetrate the waste rock’s clay cap reaching the potentially acid-forming rock below the surface before leaching acid, saline and metalliferous drainage into the groundwater. In all likelihood it will be Aboriginal people who will bear the final cost of this development project for generations to come.

Indigenous peoples of the southwest Gulf Country.

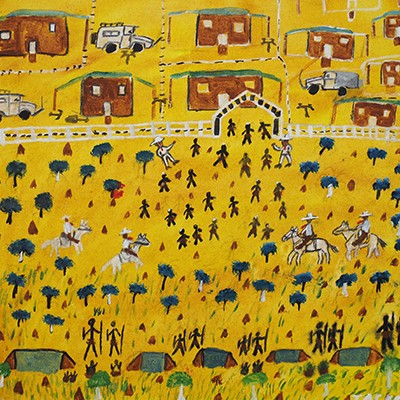

Many Aboriginal people see current policy as nothing more than government attempts to further alienate them from their kin and country and squash their long resistance to settler colonialism.

Removing Indigenous people from their land decreases the barriers to development and further opens the region to capital. And as Aboriginal people in the Gulf country say; settlers, miners, same thing.

Yardin’ Us up Like Cattle in town with no culture, Jacky Green, 2015.

‘Open Cut’ is an exhibition by Jacky Green, Seán Kerins, and Therese Ritchie that opens Saturday 24 February 2018.

The exhibition, through painting, portrait photography and a historic timeline graphic, aims to give voice and political determination to the Garawa, Gudanji, Marra and Yanyuwa peoples from the Borroloola area of the southwest Gulf of Carpentaria region of the Northern Territory, in their long struggle against pernicious development projects that detrimentally affect their lives and contaminate their ancestral countries.

Dates: 24 February to 31 March 2018

Where: The Cross Art Project, 8 Llankelly Place, Potts Point NSW.

Seán Kerins is a Fellow at the Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research at The Australian National University. Seán has worked with Indigenous Peoples and local communities for the last 25 years on cultural and natural resource management issues.

Header image 'Settlers Miners Same Thing' by Jacky Green, 2013.