Widening the conversation about adoption and foster care

Along with the benefits of these changes come complex challenges.

“It’s complicated because people are complicated,” said Amy Conley Wright, Associate Professor of Social Work and Policy Studies at the University of Sydney, in an interview for the Sydney Social Sciences and Humanities Advanced Research Centre (SSSHARC).

Wright is also director of the university’s government-funded Institute of Open Adoption Studies and new Research Centre for Children and Families, which were established to build evidence on the best interests of children in adoption and other permanent care.

Barnados Australia, a charity that supports children, pioneered adoptions from out-of-home care in the 1980s and made them open from the beginning. Open adoption has been government policy since the 1990s to maintain contact between children and their birth parents.

“The motivation behind open adoption is to address the identity needs of the young person, their need to understand where they’ve come from and have information about their origins and the reason for their adoption; to get that sense of comfort about who they are,” she said.

While adoption has declined steeply in Australia since its peak in the 1970s, the 2014 legislative change in NSW has seen some increase in children adopted by their foster parents. All forms of permanent care with relatives (kinship care) or guardianship with relatives or carers now have a legal requirement for visits with the child’s mother, father, siblings and other relatives.

More support for three-way relationships

NSW has the most children adopted from out-of-home care, 121 in 2018-2019, compared to about 20 in the rest of Australia. NSW is also encouraging permanency through guardianship (a legal order to care for a child to age 18) and kinship care, a priority for the large proportion of Indigenous children. Since the reforms, which also aim to keep children with their birth family when possible, the numbers of children in care are declining, with NSW now having the lowest rate of entry of children into care.

Wright said many mothers (and some fathers) and carers make the three-way relationship work well, but often children have been removed from their family due to concerns about abuse and neglect, usually related to parents’ mental health, drug use or domestic violence.

“We’ve seen in our research that foster carers are concerned about adopting the children in their care because of the relationship they have to manage. So we’re saying, ‘If you want more adoptions and permanent care orders you have to offer more support for relationships’.”

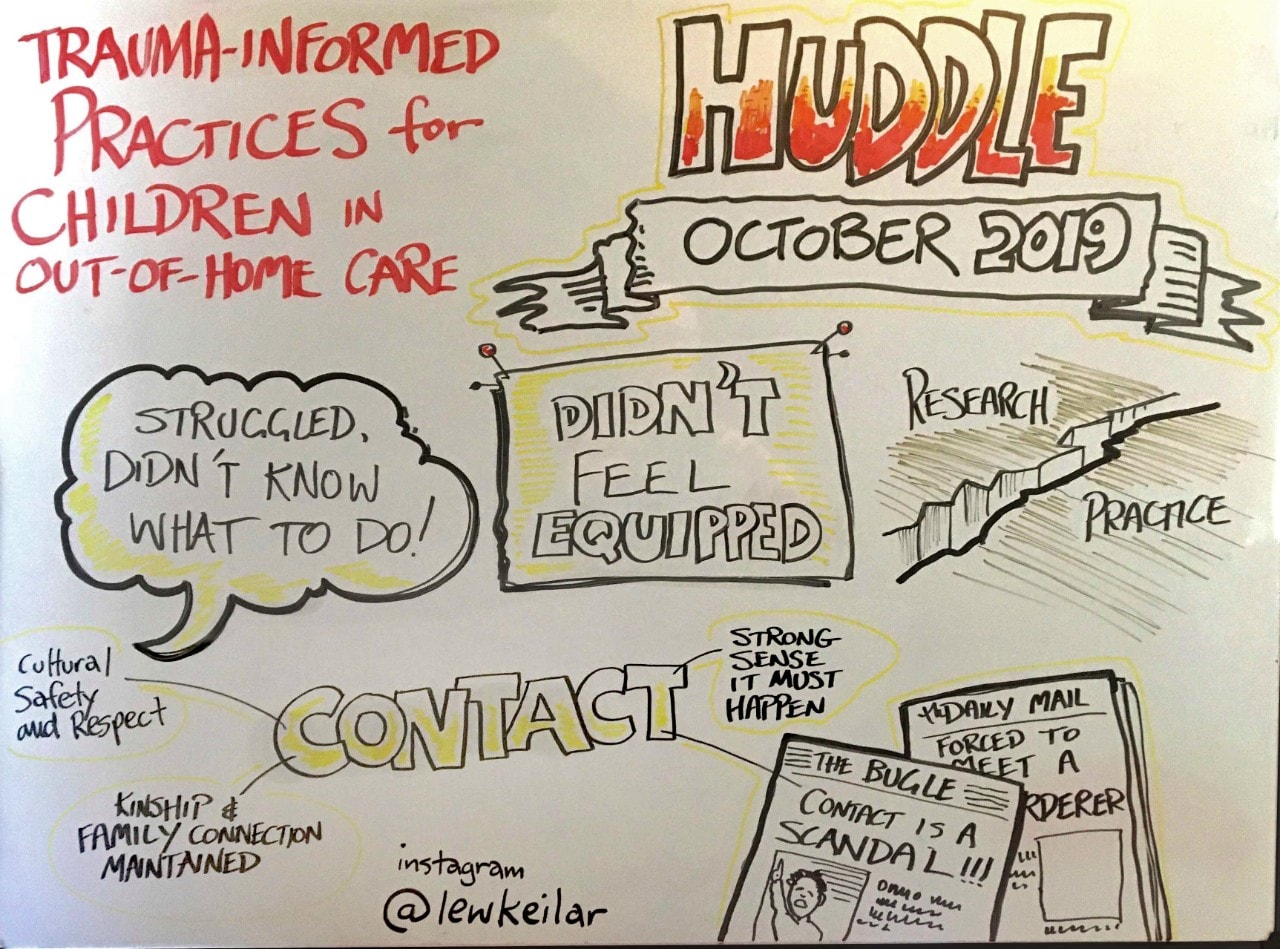

In October 2019 Wright ran a one-day Huddle at the University of Sydney to workshop “Trauma-informed practices for children in out-of-home care”, hosted by the Institute of Open Adoption Studies and SSSHARC.

A visual notetaker created striking records of the SSSHARC Huddle. Credit: Lew Keilar.

This was a prelude to Fostering Lifelong Connections for Children in Permanent Care. This three-year project funded by the Australian Research Council involves people from government and nongovernment organisations in trials of practical strategies to build positive relationships.

Wright chose SSSHARC’s Huddle format as an informal, interactive discussion group, which gathered about 25 experts in trauma and out-of-home care to help clarify ideas for the research project and act as ongoing advisors.

Academics included Emeritus Professor Judy Atkinson, an expert in inter-generational healing and recovery in Aboriginal peoples. Professionals came from bodies including the NSW Department of Communities and Justice, Legal Aid, the Supreme Court and Children’s Court, the Australian Childhood Foundation, Barnardos Australia (a partner in the Institute) and NGO partners in the project.

Too much emphasis on ticking boxes

Iman Aziza, manager of the permanency support program for CareSouth in the Illawarra region, found it useful to hear so many points of view, especially from people with long experience. Others agreed with her that increasing administrative work can affect the quality of caseworkers’ time with clients. “While we are still expected to achieve the same outcomes, there is a strong emphasis on needing to ‘tick a box’,” she said.

There were also international visitors: Mandi McDonald from Queens College, Belfast shared the experience of Northern Ireland, which has a similar adoption history to Australia and a requirement for face-to-face contact for children adopted from foster care. Three academics from Taiwan University were interested in inter-country adoption, which does not legally require contact.

“We were looking at directions for openness in inter-country adoption,” said Wright, “where you’ve got different cultures and languages and histories, and different experiences around stigma in single motherhood and relinquishing a child for adoption. How do you bridge that for openness?”

American-born Wright did her graduate studies and held positions at the University of California Berkeley and San Francisco State University before moving to Australia. She sees many parallels between the Australian and US systems but a “stark difference” is that US foster care is federally legislated and funded. There’s an emphasis on permanency throughout the country and adoption is more common than in Australia.

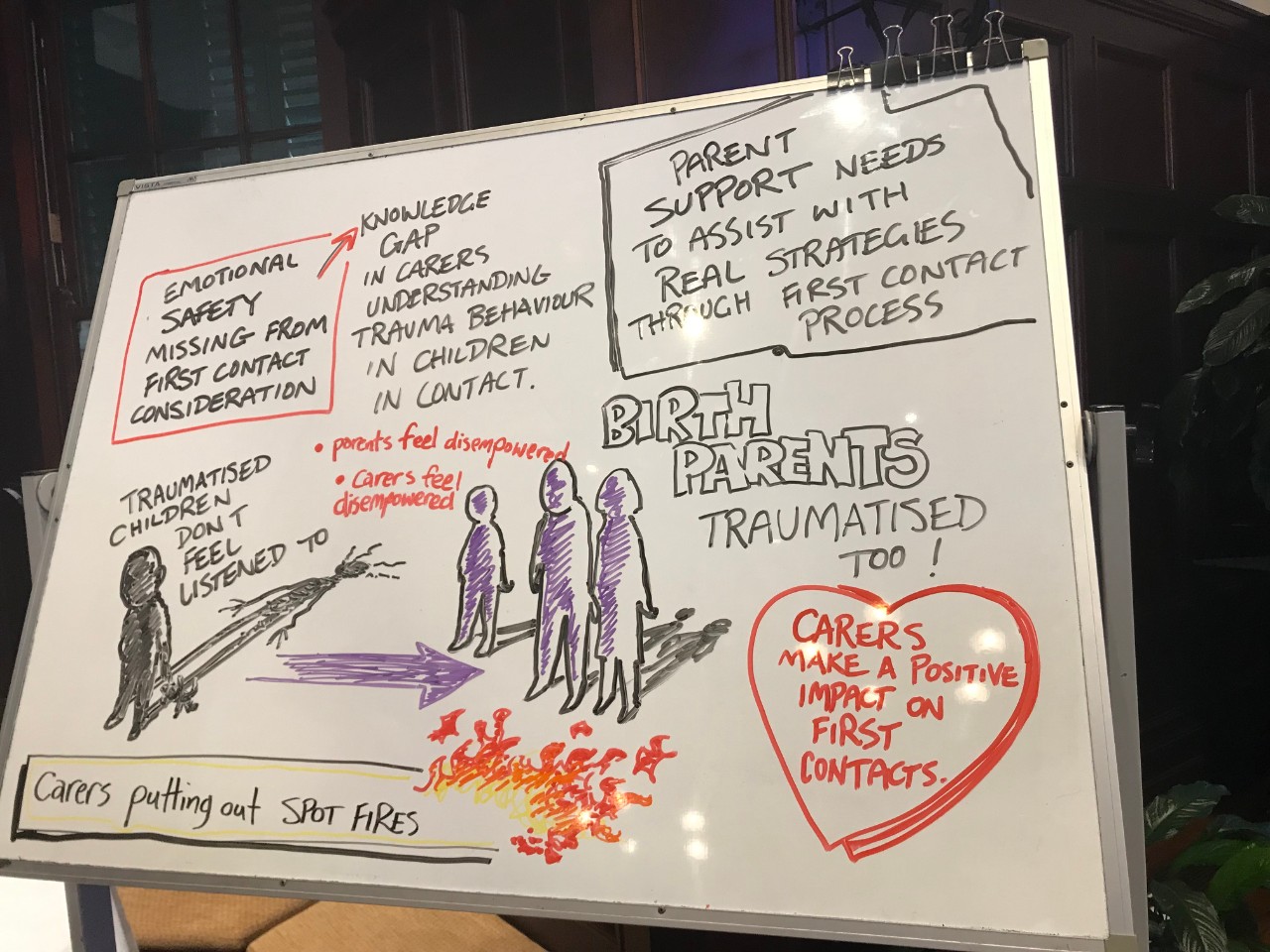

Cartoon images on a whiteboard summarised the day-long discussions. Credit: Lew Keilar.

At the heart of the Huddle was a discussion in small groups of case studies that represented the problems caseworkers encounter and how they could be improved.

For parents, Wright said, “it’s very strange to re-encounter your child being parented by someone else, in a setting where you feel like people are watching you, and maybe you have had a history of mental health issues and substance abuse. It can stir up a lot of things for people.

“We were trying to focus on how experiences of trauma are present in these relationships and can become re-triggered for children and families. We have heard from foster carers and people in the system that sometimes after children have these contact visits from their family their behaviours really change: they can become excessively clingy with their carer or they start to act out at school.”

Agencies also need guidance on how to support contact visits, and the groups addressed the question of who in the complex system should be responsible for fixing problems. “Sometimes they’ll point the finger at each other, when what is important is what is best for the child,” Wright said.

“Birth family contact” is now “family time”

Iman Aziza said her greatest concern was that “carers who have been caring for the same children long-term often don’t see the benefits of maintaining a connection to the birth family”. She learnt in discussion the “disheartening statistic” that many families and children saw each other only once a month for two or three hours.

A simple change of language at CareSouth has helped. “Supervised Contact Service” has become “Family Connections” and “birth family contact” is now “family time”. Aziza said: “The new language helps carers to understand that spending time with families should not be a sterile, supervised environment but it’s about maintaining connections, especially for siblings who don’t reside in the same placement.”

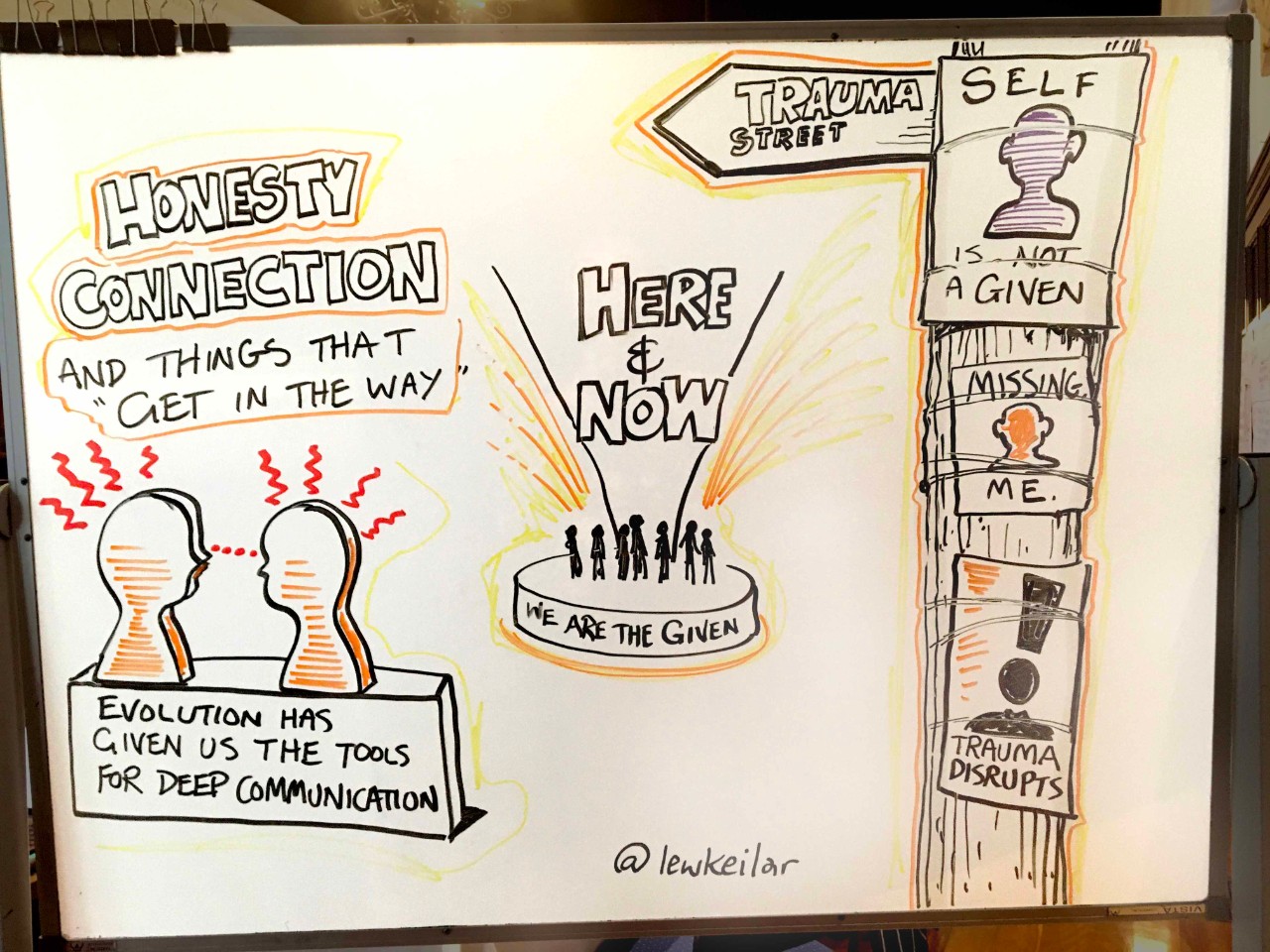

The Huddle produced documents summing up the questions and potential solutions. A visual notetaker created some striking records using text and cartoon images. They will be used in published and online resources, shared by the Fostering Lifelong Connections project with the out-of-home care sector.

Huddle records will be used in resources for the out-of-home sector. Credit: Lew Keilar.

Assessing the success of the permanency policy is “a long-term question”, Wright said. “You have to wait until they’re young adults and even older to understand how their trajectory is different from remaining long-term in out-of-home care.”

As well as collecting data from the administrative system and court records, the Institute’s staff does qualitative research by talking to mothers and, where possible, fathers, foster and kinship carers, caseworkers, and children themselves.

Wright is working with academics in other disciplines such as Sociology and Economics, where research will look at how being in out-of-home care affects a person’s human capital, especially in school achievement and employment.

“Permanency reforms, including open adoption, represent a significant and far-reaching intervention into people’s lives,” she said. “This is new territory for Australia and the way it’s done is different from other countries. We need to build up this evidence base to understand what's happening.”

The Huddle on “Trauma-informed practices for children in out-of-home care” was held on October 24, 2019 at Women’s College, the University of Sydney. A Sydney Ideas forum on Contact and Openness in Adoption was held on August 31, 2017.