Financial sector fails human rights test

Twenty-two ASX-listed financial companies, including the ‘big four’ banks and popular consumer credit provider Afterpay, are largely failing to manage the risk of potential human rights breaches.

The 2020 Financial Services Human Rights Benchmark Report, the first of its kind worldwide, assessed the performance of 22 financial companies against six human rights categories: privacy and information; anti-discrimination; economic security; health and safety; voice and participation; and right to remedy.

| AfterpayTouch | AMP |

| ANZ |

Bank of Queensland |

| Bendigo and Adelaide Bank | Challenger Financial |

| Commonwealth Bank of Australia | HUB24 |

| Insurance Australia | IOOF |

| Macquarie Group |

Magellan Financial |

| National Australia Bank (NAB) | Netwealth |

| Pendal |

Perpetual |

| Pinnacle Investment Management | Platinum Asset Management |

| QBE Insurance Ltd | Steadfast Group |

| Suncorp Group | Westpac Banking Corporation |

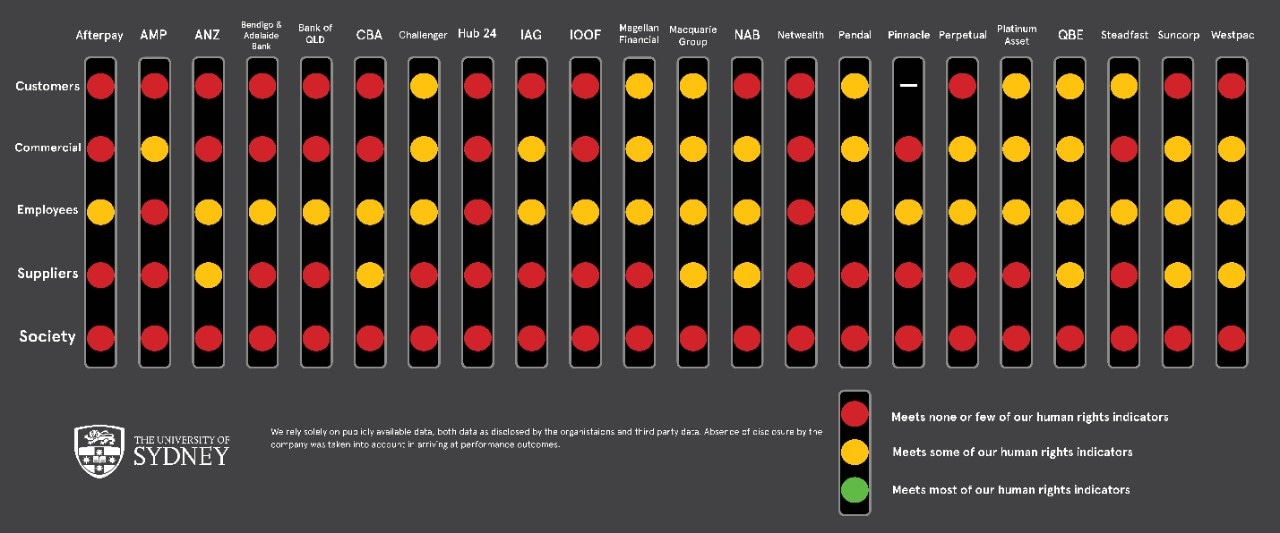

The Report authors, University of Sydney Law School researchers, rated companies’ performance in the above categories in Financial Year 2019 across five areas: retail; commercial lending investment and services; employees; suppliers and supply chain; and society.

The researchers, Professor David Kinley and Dr Kym Sheehan, found that all companies were deficient in these areas. “There are no winners or losers in this research: all of the companies can make considerable improvements,” said Professor Kinley, an internationally renowned human rights lawyer.

For example, while many have human rights policies and some have relevant due diligence procedures, none mandate that their board or key committees consider human rights, as envisaged in the UN’s Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights.

...our findings are of little surprise; the financial sector has been dogged by human rights-related incidents and issues in recent times

“This absence of board accountability and responsibility has significant implications for human rights. It is the principal reason why our traffic light system scores no green results in any of the five areas,” said Dr Sheehan, a leading corporate law expert.

“Yet our findings are of little surprise; the financial sector has been dogged by human rights-related incidents and issues in recent times. Poor treatment of retail customers, money laundering and other illicit fund uses, investments without due consideration to human rights impacts, and sexual harassment in the workplace are just some of the key issues.

“For example, last year, it was revealed that a man used an Australian bank’s money transfer system to pay for child abuse materials from Southeast Asia. More recently, there have been revelations that the recommendations that stemmed from the 2018 Banking Royal Commission – that aimed to eradicate misconduct – have largely gone unimplemented.”

Lax human rights protection risky

In addition to piecemeal human rights governance, none of the 22 companies analysed identified human rights as a key source of non-financial risk. This is despite these rights (privacy and information; anti-discrimination; economic security; health and safety; voice and participation; right to remedy) being implicit within the standard non-financial 'risk trifecta' of operational, compliance and conduct risks. “They are therefore unlikely to allocate resources to effectively minimise this risk,” notes Professor Kinley.

Dr Sheehan adds: “Having fewer or no adverse human rights impacts would decrease corporate risk. It would improve the standing of financial services companies in the eyes of their employees, suppliers, customers and broader society. It would also save billions of dollars in customer remediation costs and regulator fines.”

Missed opportunities

“The Report outcomes do not just convey a litany of failings, but also a narrative of missed opportunities,” stress Sheehan and Kinley. These arise in the ordinary course of business. For example, in the commercial lending investment and services domain, which the researchers scored amber/red for human rights, there is an opportunity to invest responsibly by exercising due diligence on the potential human rights impacts of the operations of their clients.

There are also opportunities to eradicate human rights abuses like modern slavery - which includes human trafficking, slavery, forced marriage, forced labour, debt bondage and child labour – from financial institutions’ supply chains. For instance, NAB’s FY19 disclosure indicates that environmental, social (including modern slavery), and corporate governance risk assessments were only completed for ‘Tier 1’ contracts and excluded ‘evergreen’ contracts.

Authors of the benchmark report: Dr Kym Sheehan (Corporate Law) and Prof. David Kinley (Human Rights Law).

Another opportunity relates to companies’ IT systems. “These kinds of companies spend big on tech – and tech can contribute to human rights breaches,” Dr Sheehan said. “For example, payment of remediation to wronged customers could be delayed due to outdated or unsuitable software. If companies adopt a human rights focus, IT systems can be prioritised to this end.”

Finally, one simple way to ensure that human rights risk isn’t being overlooked lies in the first line of defence: companies can provide training on human rights to front line staff and lower levels of management on what human risks look like and how to address them. “But for that to happen,” adds Dr Sheehan, “there must be human rights buy-in at the highest levels of management “.

“During the worst of COVID-19, financial companies proved that they are willing and able to speedily adapt to changing societal demands,” Professor Kinley said. “With human rights, the real challenge is persuading these companies to recognise that they are material – not marginal – to their core business interests.”

Methodology

The findings in the Report represent the culmination of three years of research and analysis. They are based on the selected companies’ 2019 financial year disclosures, as well as several third-party sources including the results of court cases for retail, commercial lending, employee and supply chain domains, and repositories such as Australian Financial Complaints Authority’s data cube for retail and Workplace Gender Equality Agency’s website for employees. All data sources are publicly disclosed information.

The authors acknowledge that their reliance on public data means that relevant private or otherwise inaccessible data may be overlooked, in which case their response is simple: such information should be made public.

Learn more about the benchmark they developed and applied to attain their findings.

Human rights performance of 22 ASX-listed financial companies

| Customers | Commercial | Employees | Suppliers | Society | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Afterpay | None/few | None/few | Some | None/few | None/few |

| AMP | None/few | Some | None/few | None/few | None/few |

| ANZ | None/few | None/few | Some | Some | None/few |

| Bendigo & Adelaide Bank | None/few | None/few | Some | None/few | None/few |

| Bank of Queensland | None/few | None/few | Some | None/few | None/few |

| CBA | None/few | None/few | Some | Some | v |

| Challenger | Some | Some | Some | None/few | None/few |

| Hub 24 | None/few | None/few | None/few | None/few | None/few |

| IAG | None/few | Some | Some | None/few | None/few |

| IOOF | None/few | None/few | Some | None/few | None/few |

| Magellan Financial | Some | Some | Some | None/few | None/few |

| Macquarie | Some | Some | Some | Some | None/few |

| NAB | None/few | Some | Some | Some | None/few |

| Netwealth | None/few | None/few | None/few | None/few | None/few |

| Pendal | Some | Some | Some | None/few | None/few |

| Pinnacle | Not applicabale | None | Some | None/few | None/few |

| Perpetual | None/few | Some | Some | None/few | None/few |

| Platinum Asset | Some | Some | Some | None/few | None/few |

| QBE | Some | Some | Some | Some | None/few |

| Steadfast | Some | None/few | Some | None/few | None/few |

| Suncorp | None/few | Some | Some | Some | None/few |

| Westpac | None/few | Some | Some | Some | None/few |

- None = meets none or few of our human rights indicators

- Some = meets some of our human rights indicators

- Most = meets most of our human rights indicators

Declaration: Funding for this project was provided by the Law Special Projects grants scheme, with a supplementary grant from the Critical Research Support Scheme in 2020.