Tracking neuroscience's impact in the courtroom

A new resource provided by the University of Sydney and Macquarie University will aid research into the emerging field of neurolaw.

Researchers says the use of neuroscientific evidence raises legal and ethical questions in the courtroom. Image: iStock

Neuroscience could reveal some of the mysteries of how humans think and behave but judges and lawyers are grappling with how it should be used in the courtroom.

Cases drawing on neuroscientific evidence have doubled in the United States between 2006 and 2009, but less is known about its impact in Australia.

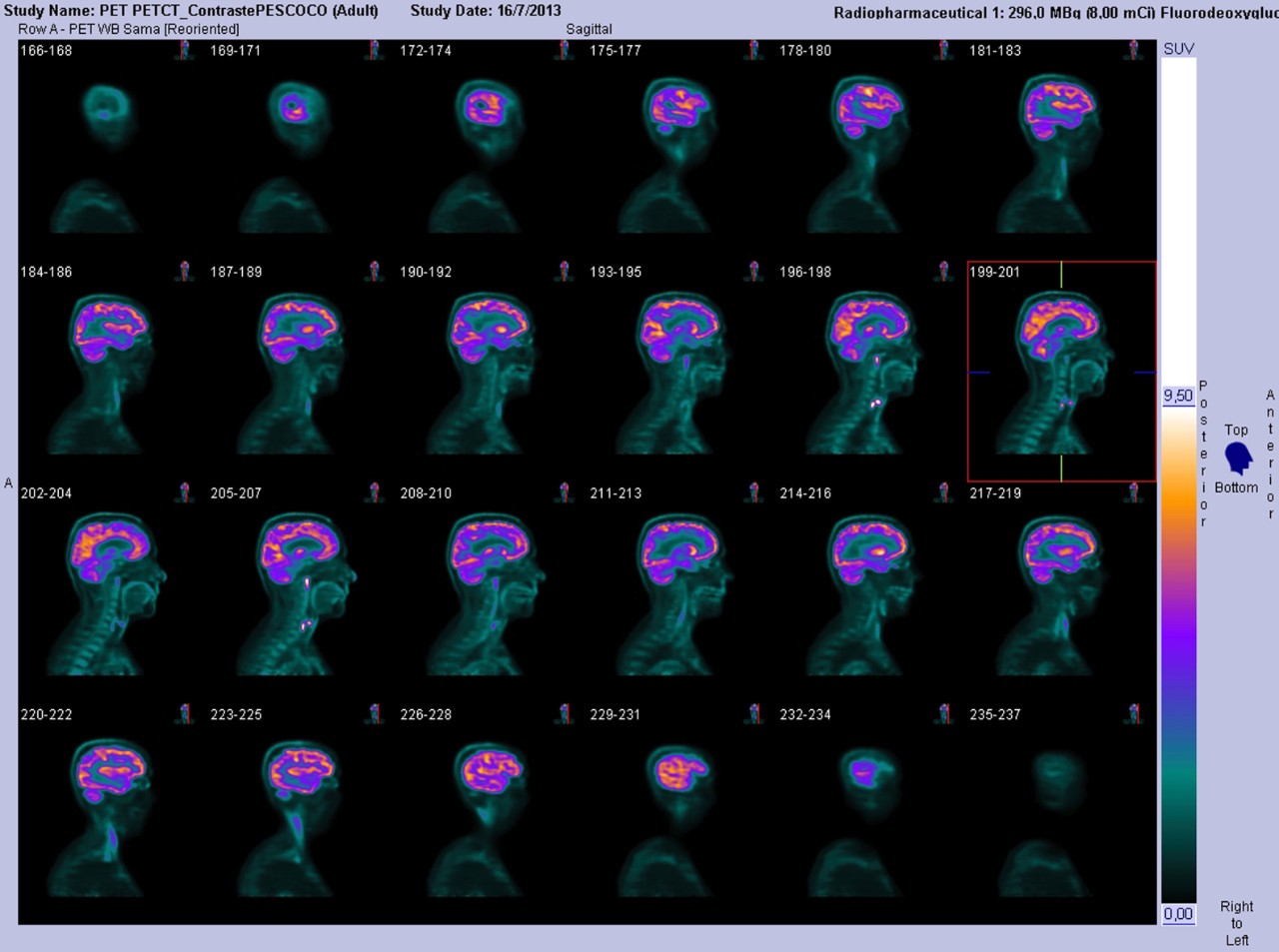

American prosecution and defence teams have called on the developing science as evidence in arguments about defendants’ responsibility and their competence to stand trial. In civil cases, brain scans are regularly being admitted to test claims of pain and suffering that have until now been difficult to prove.

Now the University of Sydney and Macquarie University have pooled their data on ‘neurolaw’ in civil and criminal cases to keep track of neuroscience’s impact in the courtroom.

Database a vital resource for legal community

Next week, Supreme Court Justice Monika Schmidt will launch the Australian Neurolaw Database, a collaboration between the University of Sydney and Macquarie University, who started the project in 2011.

In New South Wales, a recent judgment by Justice Schmidt treated post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) as a bodily injury, challenging a longstanding legal distinction between ‘mental disorders’ and physical damage – where recovering compensation for purely mental injury has traditionally been heavily circumscribed.

Meanwhile, in Victoria, a forthcoming challenge to the legality of poker machines is expected to draw heavily on gambling devices’ impact on the hard-wired rewards system in players’ brains.

What is neurolaw?

But neuroscience research is still in its infancy and the Australian legal community remains skeptical, says Dr Sascha Callaghan.

“Criminal sentences have been reduced because of evidence of the effects of brain damage caused by dementia and Parkinson’s Disease, for example. And end-of-life decisions have been informed by neuroscience evidence of consciousness, while others have turned to it to help prove the existence of injuries such as pain and the life-long effects of childhood trauma,” says Dr Callaghan.

“But despite the hype, what people do is, for the moment, still more persuasive for courts than what we can see on brain scans.”

The Australian Neurolaw Database contains a trove of Australian cases using neuroscience evidence spanning sentencing outcomes, capacity to give testimony, and end-of-life decision-making. The project has now collected upwards of 100 fully coded cases and will be continually updated, with contributions from the research team, as well as students and members of the public via a wiki feature.

“The emerging field known as neurolaw raises so many ethical and legal issues that it is important that we be aware of the direction the courts are moving in,” says Dr Allan McCay, a lecturer in Criminal Law at the University of Sydney and senior researcher at the Centre for Agency Values and Ethics (CAVE) at Macquarie University.

The researchers seek to partner with overseas counterparts to develop an integrated international database for neurolaw.