Books that changed my mind

An advanced science student and a creative writing lecturer each talk about a key book that gave them a new insight or opened them up to a new way of thinking.

Ethan Butson

He’s still studying advanced science, but Ethan Butson has runs on the board as a researcher and inventor, including systems for the management of vision impairment and the side effects of radiotherapy. His work has won awards, but his key motivation is always to help people.

The Screwtape Letters, CS Lewis (1942)

The Screwtape Letters is one of those books that seems to be so realistic that it should not be considered fiction. It is a series of letters from Screwtape, a “senior tempter” to his nephew Wormwood. Wormwood is assigned to a newly edged Christian, known only as “the patient”, to tempt the patient away from God, and to deliver him to “Our Father Below”... I forgot to mention that both Wormwood and Screwtape are demons.

The letters from Uncle Screwtape, also known by his title “His Abysmal Sublimity Under-Secretary Screwtape”, are regarding his nephew’s most recent exploits in the manipulation of the patient’s mindset. He offers advice on how Wormwood might improve his methods. Screwtape’s understanding of the human mentality is unerringly accurate, and manages to point out numerous problems that I myself have experienced, as well as divulging the reasons behind their use. As Screwtape says: “It is funny how mortals always picture us as putting things into their minds: in reality our best work is done by keeping things out.” With many such insights, I have used this book as much as a “self-help” guide, as for pleasure, if not more so.

It would seem that Lewis’s main aim with this book was to expose the human mentality and express the supernatural realm through an analysis of his own internal person. Many of Screwtape’s responses are quite chilling, and should act as cautionary advice to readers as they contemplate aspects of their own lives.

More importantly, Wormwood’s continued failures with the patient and the perseverance of the patient himself lead to the patient’s complete salvation, making him untouchable by any of the characters. This is the peak of attainment within Christianity: the overriding love of God that will overcome all temptations.

Beth Yahp

Beth Yahp isn’t just a reader, she’s a writer and a teacher of writing. She’s currently a lecturer in the University’s Master of Creative Writing Program, but across 25 years she has published fiction and non-fiction that has been translated into a number of languages, and written a libretto for an APRA award-winning classical composition.

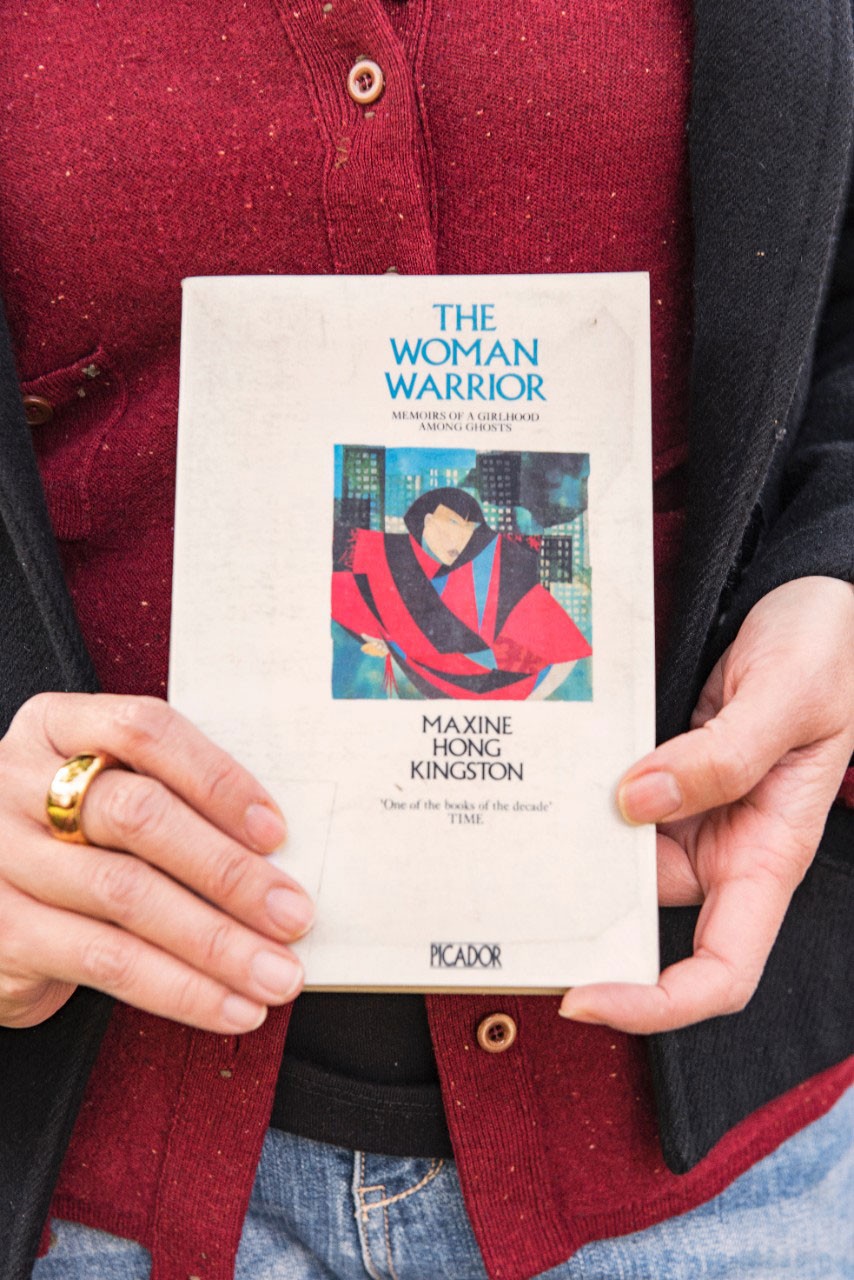

The Woman Warrior, Maxine Hong Kingston

“You must not tell anyone what I am about to tell you,” the mother insists in Maxine Hong Kingston’s The Woman Warrior. In Malaysia, as a 16-year-old avid reader with secret aspirations to become a writer, these words were familiar enough. They echoed widely held beliefs in my family and in our country that speaking about ‘sensitive issues’– such as race-based inequalities – could land you in jail, indefinitely, without a trial.

I first came across these words in a Kuala Lumpur bookshop that I haunted as a schoolgirl in the late 1970s and early ’80s. I’d never heard of Maxine Hong Kingston, a Chinese-American author, but her “memoir of a girlhood amongst ghosts” seemed to match mine so completely that it changed not only my mind but opened up the world – immediately, irrevocably.

This book, with its vengeful ghosts, sword-wielding woman warriors (my childhood dream), and weary fathers and mothers working punishing hours to feed ungrateful children (my childhood reality), reflected a world very different to the one I’d believed could be written in English.

It’s embarrassing now, but back then I didn’t think heroes and heroines in the English language could look like me or bring to life the stories around me.

In the Woman Warrior’s world and mine, children translated their parents’ ‘broken English’ and eavesdropped on forbidden talk-story sessions. But in Kingston’s world this forbidden talk could be written, captured courageously and beautifully, on the page. A no-name aunt, erased from the family history, could be given a story. A writer could “tell” and “not tell” simultaneously. In Malaysia, this still seems necessary.

“I learned to make my mind large, as the universe is large, so that there is room for paradoxes,” the mother explains in The Woman Warrior, and I understood.

I knew what I had to do.