When east meets west

Architecture students from Sydney and Indonesia came together to design shelters for Indonesian street vendors. The project saw them find new ways of using locally available materials and cross-cultural ways of problem solving.

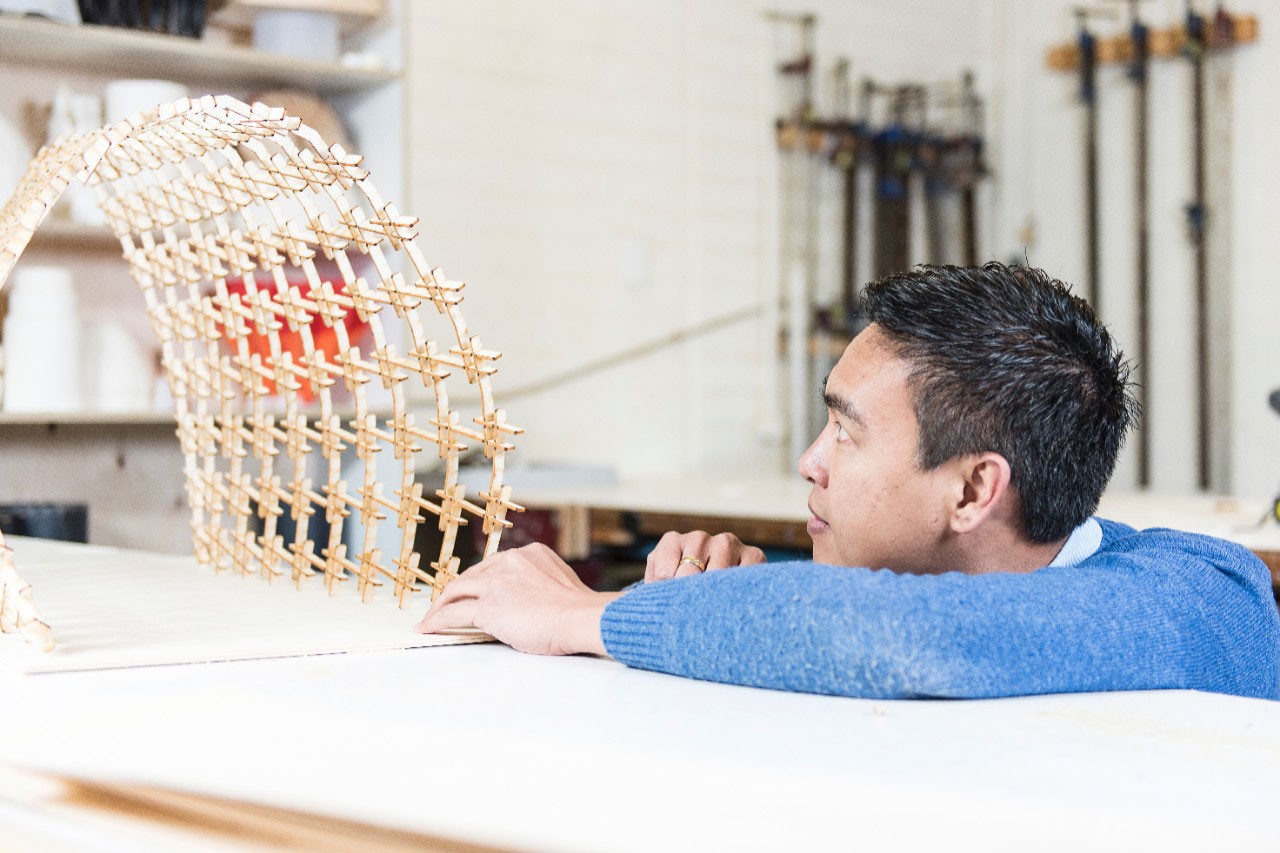

Dr Rizal Muslimin looks at new ways to create usable, portable structures.

Informal street vendors are vital to the economy of Bandung, Indonesia’s third largest city, selling affordable food and other goods and creating valuable employment.

But by setting up on footpaths, the vendors also cause signifcant congestion, and the stalls are often unattractive and hard to move. This makes the vendors a contentious issue for the local council that has made many attempts to regulate them.

Having spent most of his adult life in Bandung, renowned Indonesian architect Dr Rizal Muslimin saw an opportunity.

“Some of the vendors’ stalls don’t follow the regulations, and the way of getting rid of them can lead to tragedies. I tried to come to this as an academic, with no political motivation.”

When he joined the University of Sydney as a lecturer, Dr Muslimin knew he wanted to establish an international exchange of students. Working together, they’d create a practical shelter for street vendors, something that could possibly improve the lives of thousands, and the culture of a city.

“I had two goals,” Dr Muslimin says. “I wanted to introduce students to the problems facing informal street economies in developing cities, and teach ways to apply deployable design as part of the solution.”

The exchange began in January this year, with support from the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade’s Australian-Indonesian Institute and the Consulate General of the Republic of Indonesia. Eight students and two professors from Dr Muslimin’s former place of study and work, the Institut Teknologi Bandung (ITB), arrived in Australia to work with six University of Sydney students.

One week would be spent in Sydney designing the structures, the second in Indonesia working with the vendors to refine and construct them.

Laras Winarso, a fourth-year architecture student at ITB, was excited. “Coming from Bandung, the idea of making the street vendors look a little different in a pretty way made me interested, since it’s usually not a pretty sight to see,” she says.

The project gave Matthew Hunter a greater understanding of the materials used, and new insights into problem solving.

Divided into mixed teams, the students were tasked with designing new shelters using affordable materials that could be widely accessed in Indonesia.

“I think our differences were very useful to the process,” says Matthew Hunter (BDesArch ’15), who is currently in his final year of a Master of Architecture at the University of Sydney. “We had no idea about the requirements of the street vendors, and the ITB students were able to guide us.

“Perhaps some of our naivety helped the ITB students question their own preconceptions of how a vendor’s shelter should operate, and this really helped take the design to the next level,” he says.

Winarso agrees. “Each student had different skills. I did notice that we had different ways of solving problems; however, in the end, everyone was able to work together.”

Dr Muslimin introduced the students to computational, parametric design which enabled them to quickly build, test and analyse their designs in a computer first – and save time by pursuing only those they could demonstrate would work.

“Architects need to fail, to test and come up with the best idea,” Dr Muslimin says.

The shelters were erected in a Bandung market and used by street vendors.

The University of Sydney’s Faculty of Architecture, Design and Planning also houses a world-class Design Modelling and Fabrication Lab, including a Digital Fabrication Lab complete with 3D printers and laser cutters.

“We were able to make a prototype for our ideas and actually build them on site to see how they would be used in real life,” Winarso explains.

Winarso and Hunter worked in the same team, designing a beautiful umbrella-like shelter described by Dr Muslimin as a “deployable structure pushed to the limit”.

“The design evolved as we examined the material properties of bamboo and worked through different iterations and configurations of joints,” Hunter explains.

According to Dr Muslimin, the team harnessed the potential of bamboo in an unprecedented way, with computer simulations testing and verifying their decisions through the process.

Hunter compares the structure to a “blossoming ower” or “bunga” in Indonesian, appropriate given Bandung is also nicknamed “kota kembang”, the “flower city”. It can attach to a pole or a street lamp, and easily folds away when not in use.

Once in Bandung, the students scoured the city for spaces dedicated to pedestrians, where they could set up their structures. Conveniently, one such location was directly opposite ITB’s campus. Eager to obtain the support of the vendors, students and professors at ITB negotiated with the local leader of the vendors for permission and for help to install the shelters.

Hunter says: “I think the vendors were a bit confused at first, but after they saw our designs they were very welcoming. They had some very valid comments and pointed out some obvious design flaws, but overall seemed truly touched that we as designers were trying to improve their day-to-day life. It was an unreal feeling seeing the structure go up, and a huge relief to see it still standing the next morning.”

In fact, two structures remain in place. The third, says Dr Muslimin, was “so portable it’s gone – whoosh!”

For the students, the exchange was a genuinely inspiring experience. For Dr Muslimin himself, the results were beyond expectations. “This was about students having the real-life experience of building in a real context, and talking to the vendors, their clients, about what they want. We can’t teach that – you have to be immersed in it. Next time the students are in a similar position they’ll be wiser,” he says.

The experience has also informed Dr Muslimin’s design philosophy. “It’s a big question for me. What does it mean for a foreigner to come to our country and bring their ideas to our way of life?” he asks.

“I think it offers a new way of seeing things. Some people have tunnel vision, and sometimes we need assistance from others who have never been in that tunnel.”

Written by Rachel Fergus

Photography by Fauzan Al Agirachman and Stefanie Zingsheim