Brain training (CCT) may help fight dementia: research

A meta-analysis has found that brain training - or Computerised Cognitive Training (CCT) - can improve memory in people with mild cognitive impairment, suggesting it may prevent dementia, which can take hold within a year.

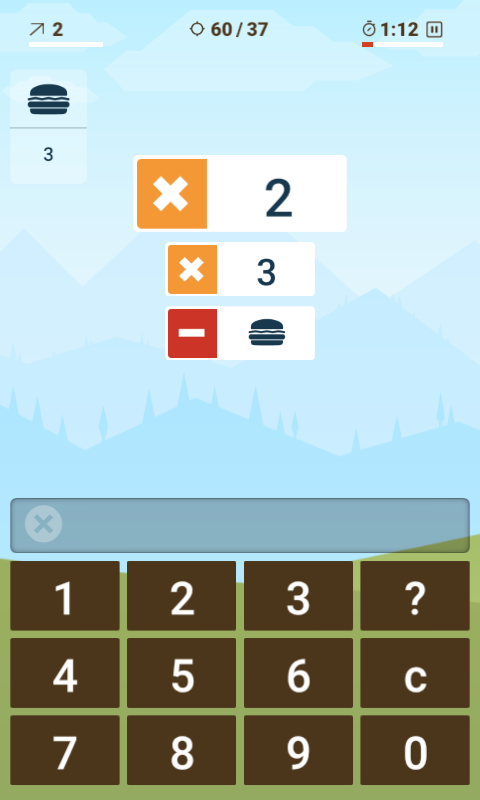

Brain training image credit NeuroNation.com. Photo at top of page: Dr Lampit in his brain training lab.

Researchers at the University of Sydney have found that engaging in computer-based brain training can improve memory and mood in older adults with mild cognitive impairment – but training is no longer effective once a dementia diagnosis has been made.

The team, comprising researchers from the Brain and Mind Centre , reviewed more than 20 years of research and showed that brain training could lead to improvements in global cognition, memory, learning and attention, as well as psychosocial functioning (mood and self-perceived quality of life) in people with mild cognitive impairment.

Conversely, when data from 12 studies of brain training in people with dementia was combined, results were not positive.

The results are published today in the prestigious American Journal of Psychiatry.

Mild cognitive impairment involves a decline in memory and other thinking skills despite generally intact daily living skills, and is one of strongest risk factors for dementia. People with mild cognitive impairment are at one-in-10 risk of developing dementia within a year – and the risk is markedly higher among those with depression.

Brain training is a treatment for enhancing memory and thinking skills by practising mentally challenging computer-based exercises – which are designed to look and feel like video games.

Dr Amit Lampit from the School of Psychology, who led the study said the results showed brain training could play an important role in helping to prevent dementia.

“Our research shows that brain training can maintain or even improve cognitive skills among older people at very high risk of cognitive decline – and it’s an inexpensive and safe treatment,” Dr Lampit said.

To arrive at their conclusions, the team combined outcomes from 17 randomised clinical trials including nearly 700 participants, using a mathematical approach called meta-analysis, widely recognised as the highest level of medical evidence.

The team has used meta-analysis before to show that brain training is useful in other populations, such as healthy older adults and those with Parkinson’s disease.

Associate Professor Michael Valenzuela, leader of the Regenerative Neuroscience Group at the Brain and Mind Centre, believes new technology is the key to moving the field forward.

“The great challenges in this area are maintaining training gains over the long term and moving this treatment out of the clinic and into people’s homes,” Associate Professor Valenzuela said.

Associate Professor Valenzuela is one of the leaders of the multi-million-dollar Australian Maintain your Brain trial that will test if a tailored program of lifestyle modification, including weekly brain training over four years, can prevent dementia in a group of 18,000 older adults.

What is a meta-analysis?

A meta-analysis is a statistical technique that begins by searching for all possible studies on a precise question, assessing their quality, and then mathematically combining these to produce an overall numerical result. Meta-analysis can allows researchers to identify fundamental characteristics of the studies that are contributing to the overall pattern of results.

What is brain training?

Brain training is a treatment for enhancing memory and thinking skills by practising mentally challenging exercises on computer. Exercises are designed to look and feel like video games and are based on neuropsychological principles to target specific cognitive domains.

For a diagnosis of dementia, these conditions need to be satisfied:

- impairment on multiple cognitive domains

- a definite decline in cognitive function

- exclusion of any possible medical causes for this decline, and

- the person is no longer able to carry out day-to-day tasks.

The last criterion – being able to do one’s daily activities independently – is pivotal to distinguishing between cognitive impairment and dementia.