The Melbourne Cup needs a social licence

What are the ethical and social aspects of using animals as entertainment for horse racing? Professor Paul McGreevy, and urban geographer, Professor Phil McManus, explore.

Like or loathe horse racing, there’s no avoiding Australia’s spring racing carnival.

But the question we are asking is: does the industry need what is called a “social licence” to operate?

Australian horse racing has changed much since the early days when the first races were staged at Sydney’s Hyde Park in 1810.

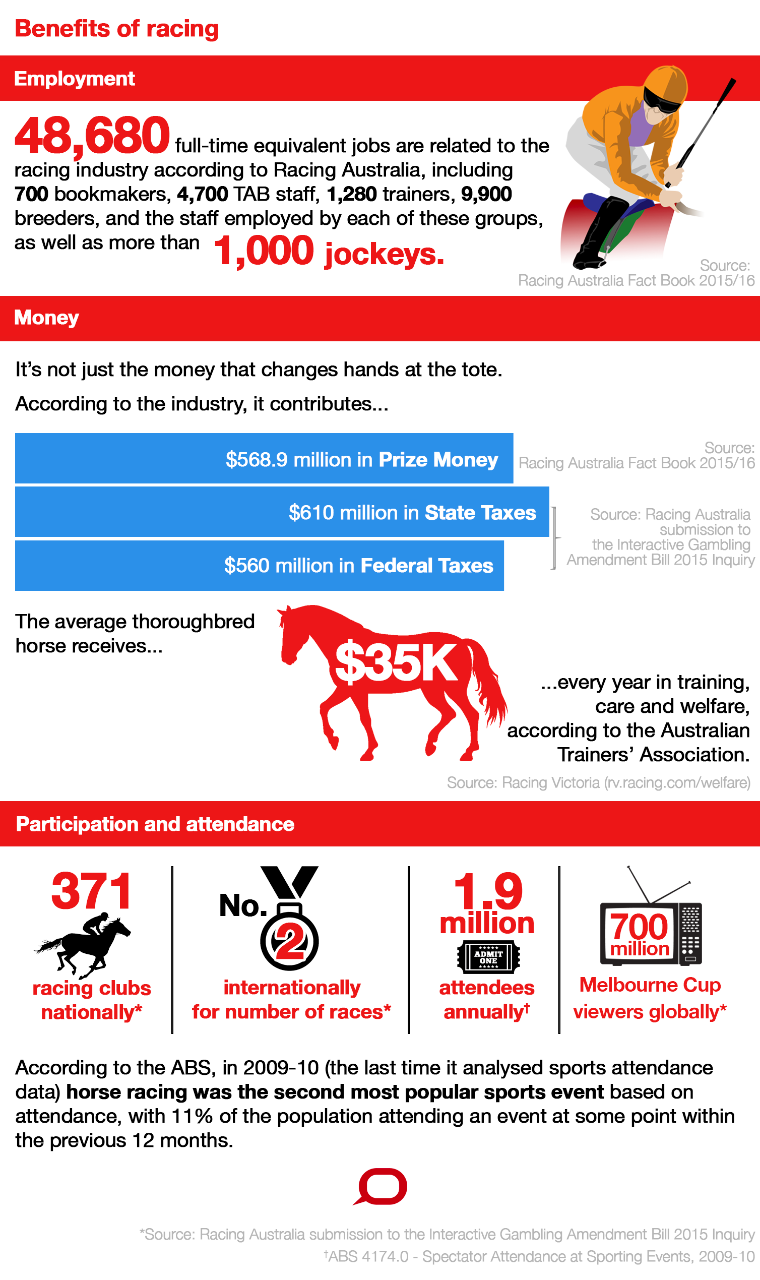

Racing Australia, which represents the nation’s thoroughbred racing fraternity, recently told a parliamentary committee that the racing industry now has more than 230,000 employees, participants and volunteers.

Horse races are watched or attended – not just on Melbourne Cup Day – by millions of people, many of whom gamble. This not only provides prize winners but also raises millions of dollars for our governments.

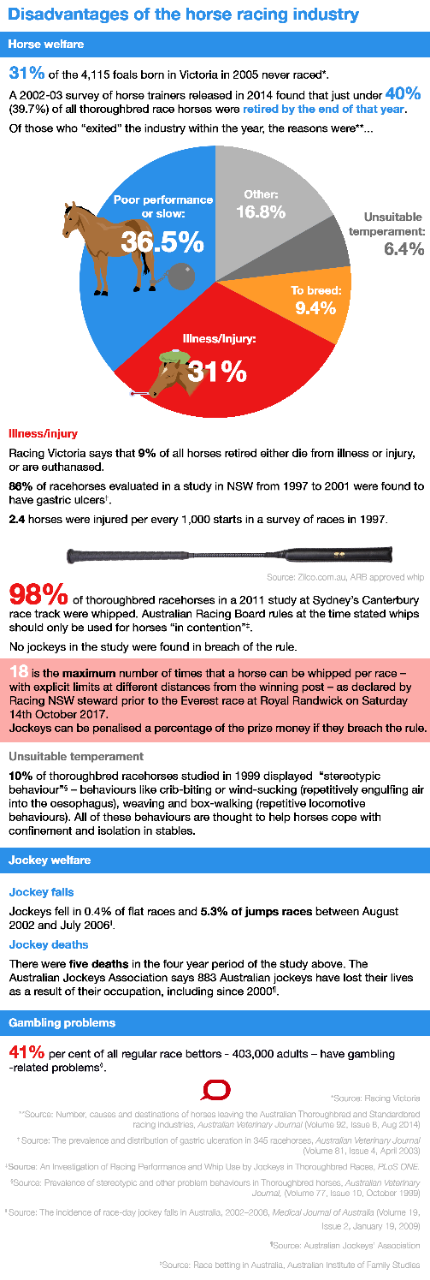

But there is also the abiding question over whether enough is being done to protect the welfare of the horses at the heart of the industry. What about the use of the whip or of tongue-ties, for example?

The racing industry recognises these issues and is aware it is being watched. As Ray Murrihy, outgoing chief steward in New South Wales, noted in 2016:

If we don’t pay due regard to welfare matters, it will be at our peril. If we don’t do it ourselves, the next time we’ll be sitting in the back seat, not the driver’s seat.

Before we consider what a social licence is and what it would mean for horse racing, let’s first consider the pros and cons of the industry itself.

As these two infographics illustrate, there are significant costs and benefits that should guide any discussions before we renegotiate the conditions under which horses are used for sport.

They also show there is a lot more data available, and some of it more recent, that highlight the benefits rather than the disadvantages of racing, and this is something we believe needs to be addressed.

To outsiders, reform may seem painfully slow. For example, it was not until 1974 that women were permitted jockey licences in Australia. Also, Australian racehorses can be whipped 18 times per race, which is ten more than their counterparts in the UK.

Insiders understand that we are all trying to do good, so perhaps the notion of what we mean by good is also changing?

The new good is about industry taking responsibility and sporting organisations recognising the horse as the chief stakeholder. These are just two of several elements feeding into the conversation around the concept of social licence to operate.

What is a social licence to operate?

Imagine an intangible, unwritten and non-legally binding social contract whereby the community gives industry the right to conduct its business. That’s a social licence to operate.

This concept of communities giving industry the right to operate (often within confined geographical limits) has existed in mining industries for several years. It has not been without controversy, given its potential to focus on local interests and exclude other stakeholders, such as those who are geographically distant.

But its application to human–animal relationships, and particularly to the use of animals in sport, is relatively new.

The issue was raised by Justice Michael McHugh in his report on greyhound racing in NSW last year when he recommended that the state’s parliament consider whether that industry had lost its “social licence” to operate.

This was greeted with dismay by Brenton Scott, chief executive of the NSW Greyhound Breeders, Owners and Trainers’ Association, who noted that the industry responds well to clear rules, legislation and policy but challenged the concept of a social licence to operate.

Who issues a social licence to operate?

A social licence to operate is said to be granted by a community or the wider society but there is no clear definition of who belongs to the community, hence the possibility of excluding wider interests. This is a core issue that currently undermines the social licence to operate of animals-in-sport organisations.

Before any formal discussion can take place among organisations and those outside the industries, there must be more explanation to those within the industries about what the concept means and how it can influence their business practices.

Conversations around a social licence to operate in the horses-in-sport domain must renegotiate current understandings, for example, practices accepted on racetracks that are illegal elsewhere, such as whipping horses.

A social licence to operate should address the conditions under which horses can partner with humans in sporting activities. It must acknowledge the risks to horses as conscripts to sport, to amateur riders as volunteers, and to jockeys as professionals.

Measuring and monitoring a social licence to operate

Discussing a social licence to operate can cause offence and it cannot take place in a vacuum of leadership, but the difficulties are multiplied if no genuine conversation takes place.

The conversation should at least include stakeholders from specific animal-based industries and from animal-protection interests. In the animal-based industries this could include a shared review of agreed metrics such as:

- industry employment;

- outreach and industry engagement on key issues;

- injuries and deaths; and

- levels of wastage.

These are just a few examples and these metrics should be published on a government portal that is publicly accessible.

Such discussions must agree on what measures of a social licence to operate represent and how they can be monitored, since in an ever-changing world we need metrics that demonstrate approval. Such metrics, for racing at least, may need to reflect some of the costs and benefits we have highlighted above, hence the need for up-to-date data on both sets of metrics.

Organisations overseeing racing and equestrianism may create ways to integrate the new good of individuals taking responsibility for improving horse and rider welfare through their everyday practices. Committing to reporting on and incrementally improving metrics of welfare may benefit everyone.

Our world is changing. Organisations that govern human-animal relationships, especially when animals are used for entertainment, will have to move with these changes or face the prospect of, as Ray Murrihy put it, “sitting in the back seat”.

This article was first published in The Conversation. Professor Paul McGreevy is Sub Dean of Animal Welfare from the School of Veterinary Science. Professor Phil McManus is Head of the School of Geosciences and Professor of Urban and Environmental Geography.