How one woman transformed the way we study the human body

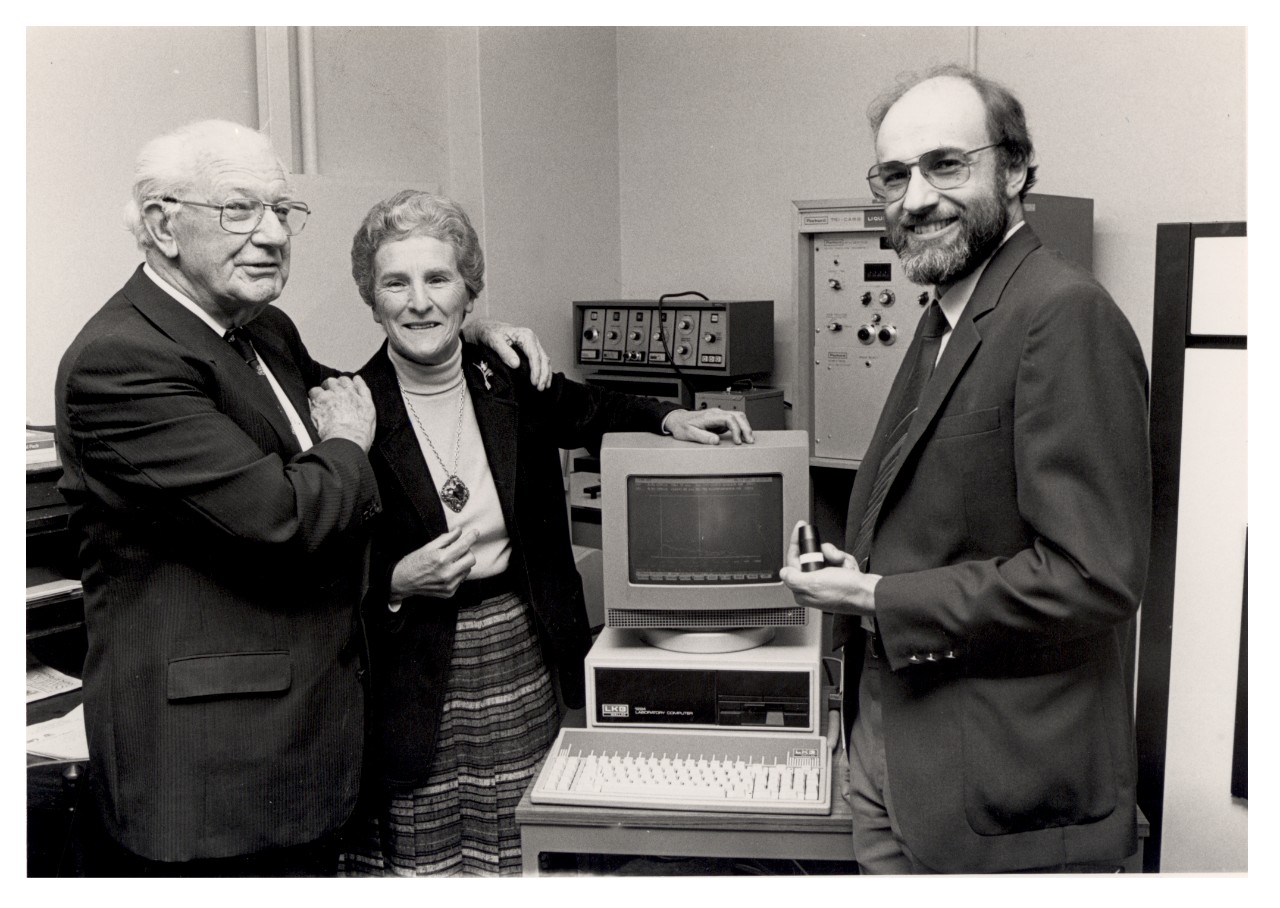

Mrs Ann Macintosh with Chancellor Sir Hermann Black, left, and Dr Mike Barbetti at the opening of the NWG Macintosh Centre for Quaternary Dating in 1984.

It is one of the most eerily beautiful rooms in the University and among the best museums of its kind. It is also closed to the public.

The JT Wilson Museum of Human Anatomy is in the grand and historic Anderson Stuart Building. It is mostly visited by anatomy and histology students, though surgeons and even artists come here looking for insights into the human body. Inside the glass cases are hands, feet and other human parts, delicately dissected to show the body’s complexity. Planning for the museum started in the 1800s, but today it is bright and modern.

If there is one person to thank for the excellent condition of the museum, it’s the late Ann Macintosh, who at one time worked in the building and later returned as a volunteer. She paid for the museum’s renovations, but there are few places in Anderson Stuart that haven’t been touched or even transformed by the generous and considered donations of this energetic, plain-speaking and beloved woman.

“She’d say, ‘Call me Ann’ but no one did,” remembers Associate Professor Kevin Keay. “She was always called Mrs Macintosh.”

When Keay started as a junior staff member in 1987, he used to bump into Mrs Macintosh in the lift. He still works in the Anderson Stuart Building, but now as the head of Anatomy and Histology. “Thanks to Mrs Macintosh we’ve been able to make upgrades that mean we can teach properly, we can research properly, we can support research,” he says. “She’s made a massive impact.”

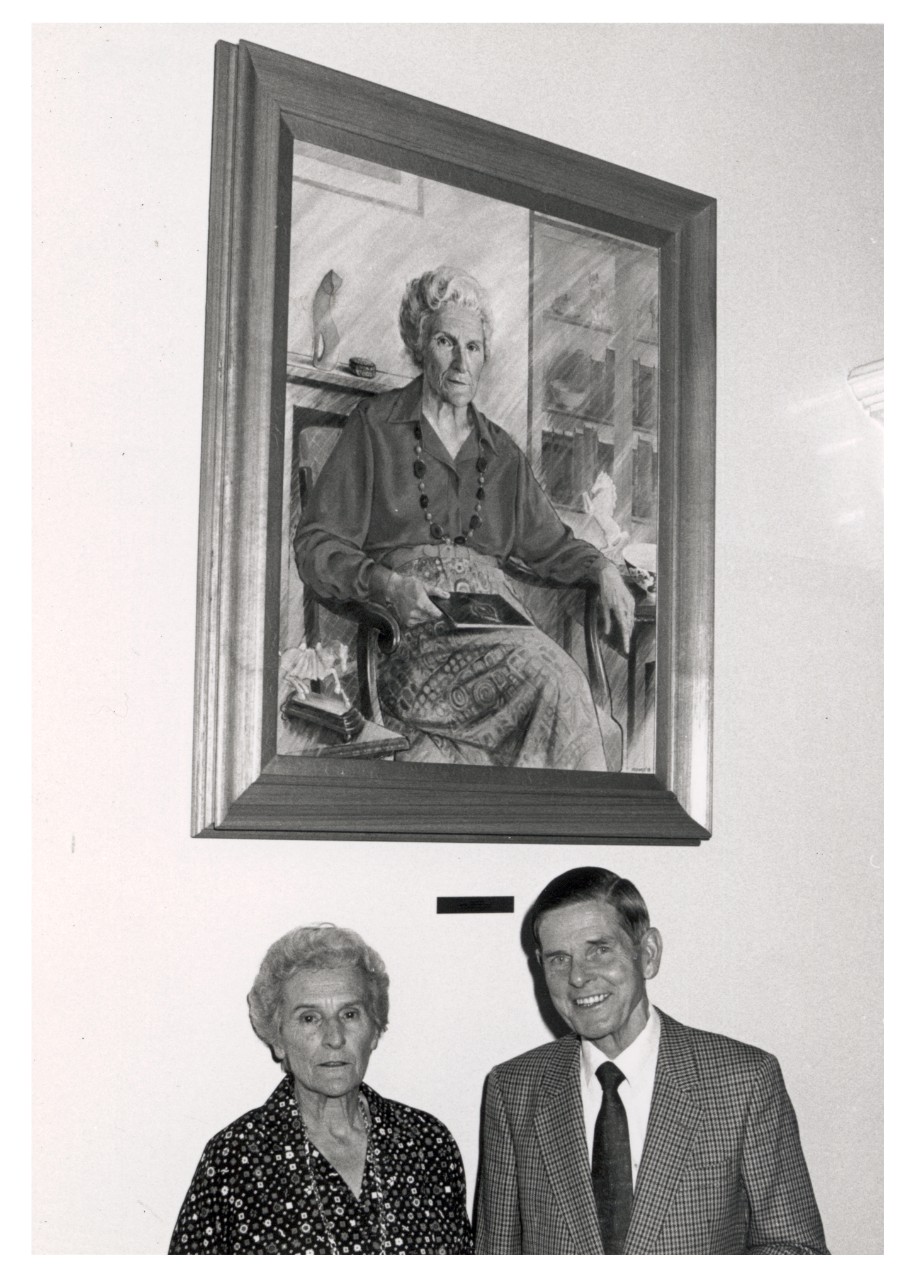

The portrait that artist Stuart Maxwell, right, painted of Ann Macintosh, left, still hangs in the Anderson Stuart Building.

The making of a benefactor

Mrs Macintosh’s connections with the University run deep. Her paternal grandfather studied at the University of Edinburgh with the Anderson Stuart (Sir Thomas Peter), and later taught in the Department of Anatomy. Her maternal grandfather was Sir Edmund Barton, who was a Fellow of the Senate in the late 1800s, before going on to become Australia’s first Prime Minister. Then there was her husband, the widely respected Professor NWG Macintosh, a Challis Professor of Anatomy.

Mrs Macintosh was Miss Ann Scot Skirving when she started as a secretary in the Department of Anatomy and Histology in 1947, before marrying the professor in 1965. As was the norm for newly married women at the time, she gave up her job, but her fascination with the department continued. When her husband died in 1977, Mrs Macintosh returned as a volunteer, spending hours cataloguing the collections.

The desk where she sat is still in the JL Shellshear Museum of Physical Anthropology and Comparative Anatomy, screened by a row of skeletons. From this vantage point – and her place at the centre of a community of staff and students – she could make astute observations of what the department and the building needed.

She was interested in outcomes, but her support was given with no strings attached.

Mrs Macintosh helped fund renovations to the Anderson Stuart Building, including those that revealed its stained-glass windows.

Revitalising a historic building

The Anderson Stuart Building opened in 1889 to house the first medical school in Australia. Over the years it lost some of its grandeur, but today its rooms are being updated sensitively, and the recently uncovered stained-glass windows bathe the hallways in light.

Mrs Macintosh helped create the momentum for the renovations, then helped fund them. Even after her death in 2011, her legacy continued to help with the upkeep through a trust.

Support for research

Keay says her donations have provided vital support for research that could not otherwise have happened. “Each year, she would give the head of the department money to support an individual activity,” he says. “The money had to be used to support a young scientist in anthropology research who wanted to pursue a less mainstream idea. She was interested in outcomes, but her support was given with no strings attached.”

It’s impossible to talk about the contribution of Mrs Macintosh during her life and through her bequest without it becoming a list: she supported research into chronic pain and reproductive biology; set up PhD scholarships; established the NWG Macintosh Centre for Quaternary Dating (to age-date ancient bones); set up the NWG Macintosh Memorial Fund to support research into Anatomy and Histology; and established the Centenary Fellowship for the travel‑based training of departmental staff.

Her name is even on the Ann Macintosh Forensic Osteology Lab which, among other things, helps police identify human remains.

While she no longer sits at her desk in the Shellshear Museum, Mrs Macintosh is still helping to shape the Anderson Stuart Building. She also shapes every medical student who studies at the University and takes that knowledge into the world.