Arts student uncovers secret history of penicillin in Australia

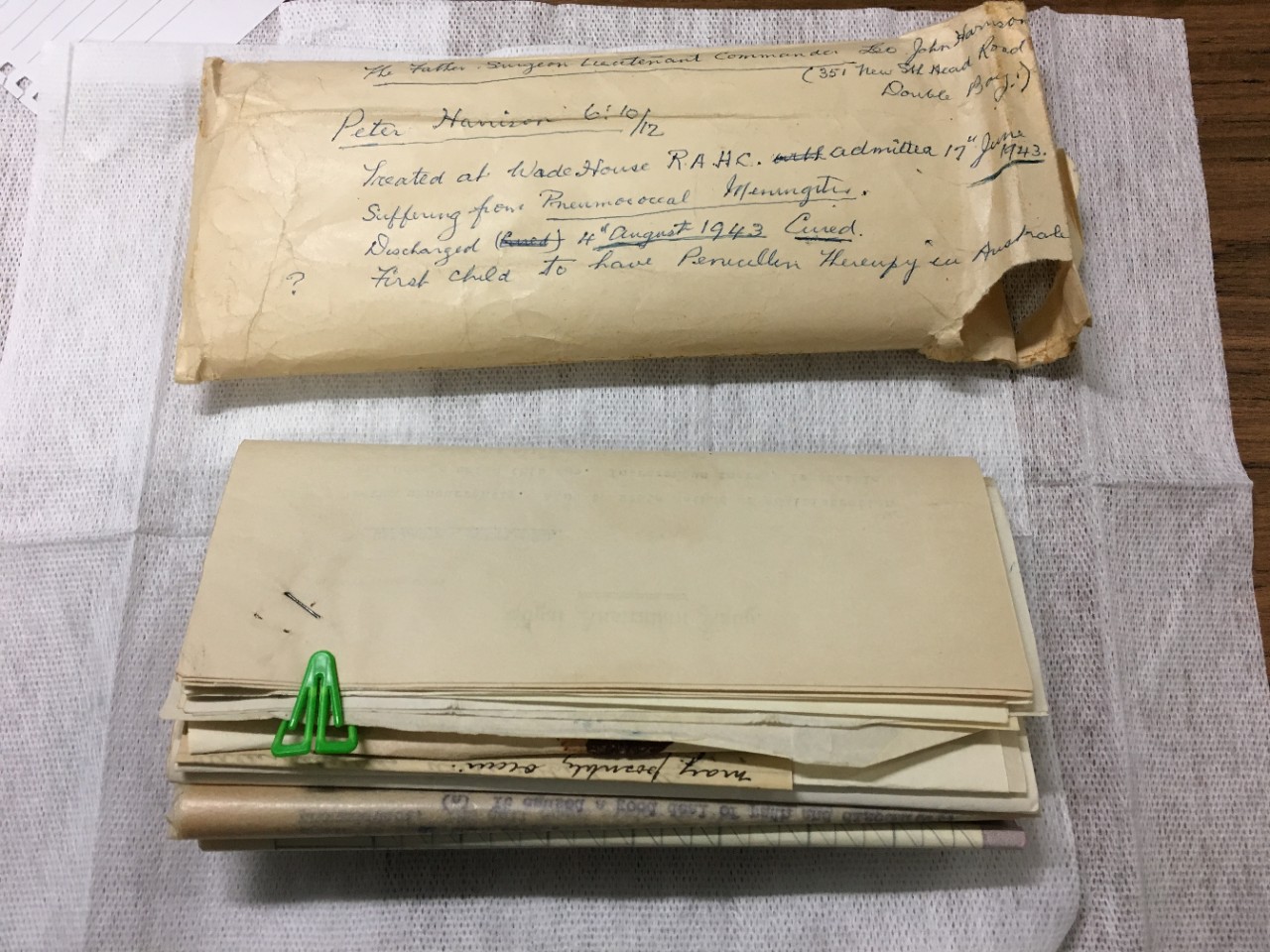

The 'Penicillin Papers'. Image courtesy: The Children's Hospital at Westmead.

An interest in medical history prompted Bethany to undertake a uniquely interdisciplinary internship at the Children’s Hospital at Westmead (CHW) as part of her Master of Museum and Heritage Studies.

While working with the hospital’s Heritage Committee – including Dr Megan Phelps from the University of Sydney Children’s Hospital at Westmead Clinical School – to preserve and protect records for posterity, Bethany uncovered evidence of an important first in Australia’s paediatric healthcare.

What she found "sitting in an envelope in the back of a safe" was a record of the first use of penicillin being used to treat an Australian civilian in 1943 – a year earlier than historians previously claimed.

"Records from the Australian War Memorial state the first use of penicillin by Australians was as a wartime drug to treat soldiers serving in Papua New Guinea in 1944," Bethany says. "The use of penicillin during the war, and Australian pharmacologist Howard Florey’s role in the development of penicillin in England, are generally believed to be the catalysts for the Australian government investing in penicillin."

However, the documents unearthed by Bethany during her internship provided an alternative timeline.

The Penicillin Papers

The ‘Penicillin Papers’ show a six-year-old child had been admitted to the CHW – then known as the Royal Alexandra Hospital for Children – with pneumococcal meningitis and was not responding to usual treatments, so his doctors reached out to their counterparts in the US for help.

"Penicillin was slowly introduced in the United States in 1943, though limited amounts were being produced," Bethany says.

Despite the shortage, the papers show a small batch of penicillin was shipped in dry ice from the US to Sydney, via Brisbane, on a bomber plane.

The drug provided immediate benefit: "his chart fell immediately from 105 degrees to 96 degrees in 24 hours, and doctors noted that "the child's general condition improved amazingly".

However, "the papers show boy's symptoms returned after a week and a second request for penicillin was made," Bethany says.

As penicillin stocks were in "meagre supply", the US provided a second medication, that of anti-pneumococcal serum which was given along with another round of Sulphadiazine treatment. After a long three months of treatment, the boy was discharged from Hospital on 4 August 1953 "completely cured".

Bethany says the Penicillin Papers contained enthusiastic recommendations from doctors in the United States and Australia, arguing the success of their treatment of the boy proved they should start growing the mould in Australia.

"According to the Penicillin Papers, it can now more accurately be said that it was this case that became the catalyst for the introduction of penicillin in Australia," she says.

A well-kept secret

In spite of its significant historical impact the success story was deliberately kept secret, Bethany says.

"The papers show doctors requested a censure as they would be unable to treat other patients with their limited supply of penicillin," she says.

The only mysteries remaining were why the doctors chose to treat this particular child with penicillin and whether he was still alive.

"He certainly wasn’t the only child at the time who had been diagnosed with pneumococcal meningitis – but unfortunately initial letters from the doctors requesting the penicillin from their US counterparts weren't found in the Penicillin Papers," Bethany says.

Bethany assembled a rough timeline: "I realised that if the boy was six years old in 1943 he would now be in his early eighties and could very well still be alive – I decided I wanted to try and track him down."

Bethany Robinson (second from right) with Peter Harrison (far right) and his family.

Meeting ‘the boy’

Bethany tracked the boy down, with the help of hospital staff and resources. She found Peter Harrison, an 82-year old father of three, in Tamworth. Their meeting was recorded by ABC’s current affairs program 7.30 and shed light on the mystery of why Peter was treated with penicillin.

"Since meeting Peter, he has confirmed his father was a senior sergeant in the Australian Royal Navy and very capable of pulling strings. It is very possible Peter was just fortunate his dad held such a high rank in the navy," Bethany says.

"Of course, the fact that many of the doctors and hospital staff may have come across penicillin whilst on war service could have also been a contributor."

A uniquely interdisciplinary experience

It’s an incredible story and one that Bethany isn’t finished telling. She recently completed her Master of Museum and Heritage Studies and says the Children’s Hospital at Westmead has applied for a heritage grant that, if successful, will help her to continue her research.

"The Children's Hospital at Westmead might not seem like the obvious choice for a museum and heritage studies internship," Bethany says, "But I can honestly say I am so lucky to have had this experience and the opportunity to use my skills in collection management, cataloguing and heritage management in such a unique and historically important context.".

Bethany's supervisor at the CHW, Carole Best, says the placement was pivotal in the discovery of the Penicillin Papers: "Because everyone on the Heritage Committee has other jobs to do, having a student arrive on our doorstep ready with an agreed project meant we needed to reprioritise our other responsibilities to accommodate her needs.

"We wanted to provide Bethany with a legitimate experience and use her skills to our advantage, so we were committed to exploring the contents of the archive in detail. Without Bethany, the Penicillin Papers would still be unread inside a dark safe."

Read more about the Penicillin Papers on the Sydney Children's Hospitals Network website.