When politics corrupts the fairness of elections

I remember laughing when Guns N’ Roses said they would release an album called Chinese Democracy, because it was so clearly an oxymoron. I never thought “American democracy” might end up with the same fate.

In 2008, I boarded a plane to a country I had long revered: the United States of America. I arrived in New York ready to study constitutional law and to experience firsthand the country that had influenced so much of my life, my country and, frankly, the world.

Obamamania had gripped young people everywhere, including me, so I asked if I could help out in the November election, even though I was a foreigner. I was told that one useful role I could perform involved voter protection. “What do voters need protection against?” I wondered.

I found out when I was assigned to a polling place in Virginia. The weekend before Election Day, signs posted around the black neighbourhoods – falsely suggesting they had been issued by an election authority – warned voters that unprecedented turnout was expected, and so to handle the crowds, Republicans would vote on Tuesday and Democrats would vote on Wednesday.

My heart sank. Spreading misinformation to suppress the vote was something I expected in Russia or Venezuela, but not America. I had come to learn about constitutions and democracy from the country that invented the former and exported the latter. But, with voter suppression rife, could it be that this country wasn’t even a democracy?

As I applied for a two-year work visa in 2009, I had no idea I was about to witness a period of the most extreme gerrymandering in modern American history.

America conducts a census every 10 years in the zero year (2000, 2010 etc), and redistricting occurs in the year following. Redistricting means drawing the electorate boundaries for things like congressional or state legislative districts.

In 2012, 1.4 million more people voted for Democratic candidates for Congress, yet the Republicans wound up with 33 more seats.

In 2011, I witnessed a redistricting frenzy. Democrats and Republicans across the nation retreated to secret locked rooms with computers and voting data for everyone in the country. With surgical precision, they divided up voters into districts designed to secure advantage for one side for the next decade. In the places where they did a good job, elections would become almost irrelevant, an afterthought.

For example, in 2012, 1.4 million more people voted for Democratic candidates for Congress, yet the Republicans wound up with 33 more seats.

How did this happen?

America, unlike Australia and the rest of the sane world, has not switched to using independent people to redraw district lines. The very people who will run for office get to draw the districts from which they will run. That is, the politicians get to choose their voters, not the other way around. It is madness.

In some states, people are able to fight back through referenda, and demand independent redistricting commissions. Places like Arizona and California were early adopters, and this year four more states (Michigan, Colorado, Utah and Missouri) will vote on whether to change to the commission model. But for the states that don’t allow citizens’ ballot initiatives, there seemed to be no hope.

Enter Nicholas Stephanopoulos. He started as my boyfriend, then became my co-counsel, and is now my husband. He thought we could set a national judicial standard declaring partisan gerrymandering unconstitutional. The Supreme Court had toyed with the idea since 1986, but most people thought it was a lost cause. I didn’t. I knew America could do things differently because I come from a country that got beyond the “Bjelkemander” (a word referencing Queensland premier Joh Bjelke-Petersen, who benefited from a notorious gerrymander in the 1970s and 1980s).

Ruth Greenwood.

Nick and I teamed up to argue that the federal constitution prohibits partisan gerrymandering and that it can be measured using political science metrics. Nick, the academic, wrote the briefs. I, the advocate and trial lawyer, took depositions, cross-examined witnesses and garnered support in the media from both Democrats and Republicans.

We became the first plaintiffs to win a partisan gerrymandering case at trial, with co-counsel from Wisconsin. The decision was appealed, and due to a quirk in federal law, the appeal went directly to the Supreme Court of the United States. We expected either outright rejection or, preferably, resounding victory. Instead, in June 2018, the Supreme Court used a procedural issue called “standing” to kick the can down the road – sending us back to the trial court to add more information to the record, before it will rule on the merits of the case.

Luckily for us, we have another case with a more developed factual record that is likely to be finalised in the coming months, and will probably end up back at the Supreme Court in the October 2018 to May 2019 term.

Unluckily for us, Justice Kennedy – the so-called “swing” justice, because as a conservative, he made a number of unexpectedly progressive judgements – suddenly retired in late June. President Trump is likely to appoint an extremely conservative new member to the Court.

But I’m not giving up just yet. I hope we win. I hope America stops being “exceptional” in letting politicians draw their own district boundaries. I hope the voices and the votes of the people can be equally acknowledged. But even if we lose, I’ll keep looking for new ways to improve the system.

American democracy has been such a great experiment for more than two hundred years. It would be a shame to lose it all now.

Written by Ruth Greenwood (BSci (Hons) ’04 LLB (Hons) ’06)

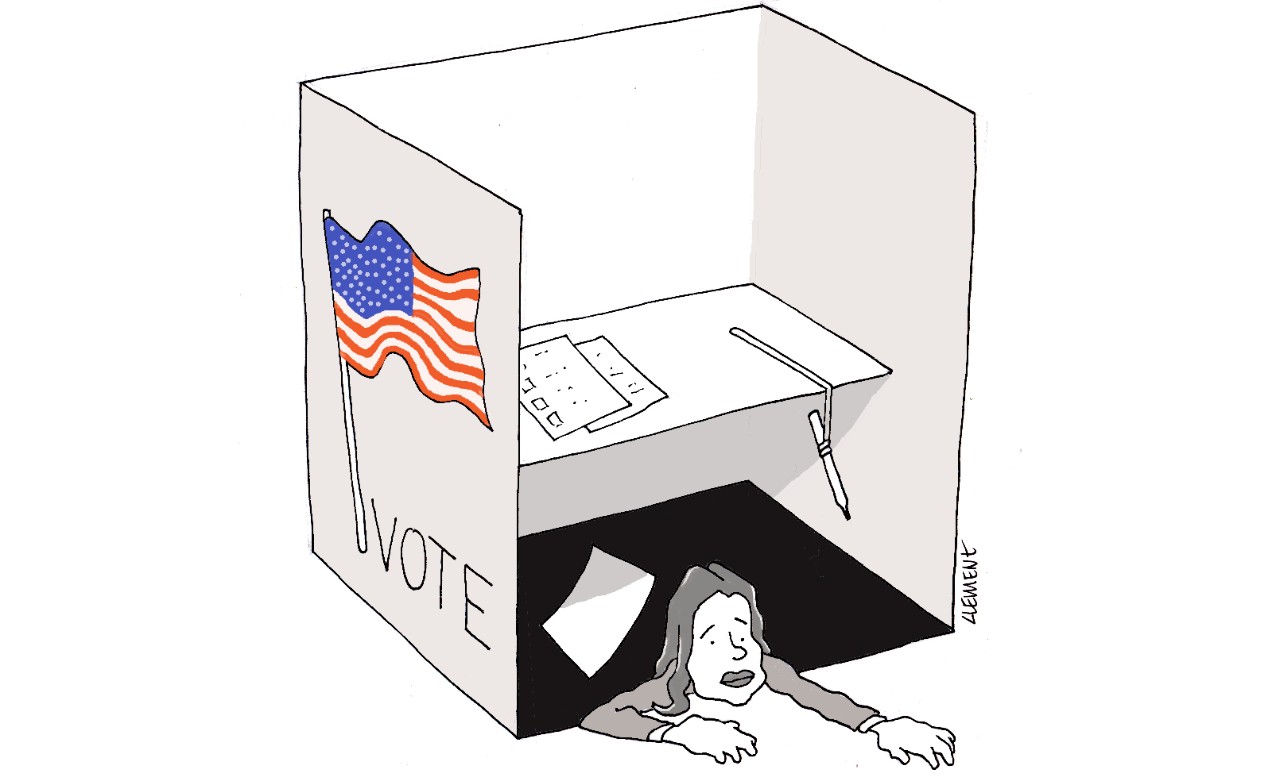

Illustrated by Rod Clement