More operations done using robotic surgery

Associate Professor Ruban Thanigasalam and Professor Paul Bannon in the Hybrid Theatre, and in the arms of their robotic team mate.

On a winter’s night in inner city Sydney, a few hundred medical professionals sit in the cavernous dining room of a refurbished railway workshop. Their eyes are glued to a giant video screen where a prostate operation is being performed live from an operating theatre elsewhere in the city.

An unusual element of the procedure is that the surgeon is sitting metres away from the patient, his head buried in a console. From there he is controlling the spidery, metal limbs of a robotic surgical unit.

The audience at this medical technology summit aren’t necessarily surprised by what they are seeing; robotic surgery is already well established. But no doubt many conversations will be had later about where the technology might take us.

What’s already certain is that the opportunities are transformative, allowing clinicians to look in new places for ideas. Research into image-guided robotic surgery and robotic automation is already well underway through collaborations with the Sydney Local Health District, robotic surgeons at Royal Prince Alfred Hospital (RPA) and the robotic surgery research unit at the RPA-Institute of Academic Surgery.

Exploration of this new technology happens in what's called the Hybrid Theatre. Buried in the deepest part of the University’s Charles Perkins Centre, it looks like a pristine science fiction movie set where three pieces of technology dominate the room.

The imposing-looking and named Artis Pheno x-ray/CT system moves with the fluidity of an industrial robot painting a car. Instead of a car, it moves around a patient as it delivers detailed 3D images even as an operation is happening.

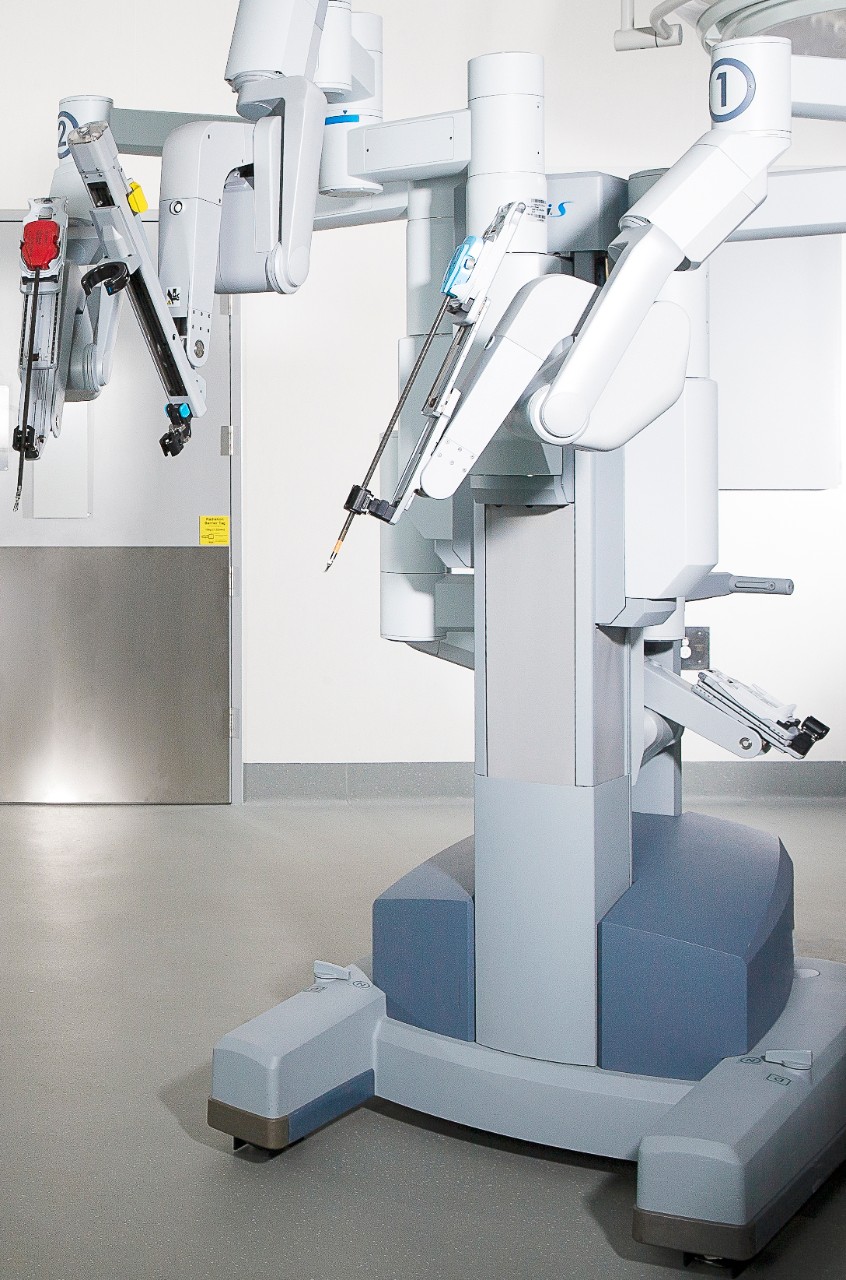

Nearby is the robot surgeon, more correctly called the da Vinci Surgical System, with its robotic arms containing high-definition cameras and customisable instruments. Beside it is a control console with hand grips that the surgeon uses to control the robotic arms, moving them with super-fine precision. It also provides a detailed, internal view of the operation.

The da Vinci console separates the surgeon from the patient, but adds an incredible level of precision.

The Hybrid Theatre operates under the umbrella of Sydney Imaging, which provides a suite of preclinical and clinical imaging techniques at the University for leading-edge biomedical research. The Hybrid Theatre itself was purpose-built to accommodate robotic surgery and image-guided surgical technologies. Its level of sophistication presents opportunities that haven’t existed in Australia before.

Looking very at home among the theatre machines is Professor Paul Bannon (MBBS ’87 PhD (Medicine) ’98). A highly regarded cardiothoracic surgeon, he holds many senior titles including Academic Director of the Hybrid Theatre itself. He is one of the people who brought it into existence to be part of the new biomedical research and surgical training precinct taking shape at the University.

“What we always do is try to work out some way of doing things better,” says Professor Bannon. “The surgical paradigm right now is minimal invasiveness. Robots are already helping us do that.”

Minimal invasiveness means faster recovery for patients with the added benefit of freeing up hospital beds. Associate Professor Ruban Thanigasalam (MS '08) is a urological and robotic surgeon, and an expert in using the da Vinci system (he also helped organise the technology summit mentioned earlier in this story), and he has seen the numbers.

“For the last 100 prostate cancer operations we have performed across the Royal Prince Alfred and Concord Repatriation Campus, we found that robot surgery meant less blood loss, shorter hospital stays and less opioid usage compared to open surgery,” he says.

As a urologist, he also has an insight into why urological surgeons were among the first to embrace using the da Vinci system, “We often have to operate deep into the pelvis which can mean holding back-bending positions for a long time when performing open surgery. That doesn’t happen with console-based, robotic procedures.”

The da Vinci Surgical System is descended from robotic technology developed by the US military in the ’80s and ’90s that was designed to operate on soldiers on the battlefield. It has been used in hospitals in Australia since 2003. There are now six at the Royal Prince Alfred Hospital and on the University of Sydney campus, including in the Hybrid Theatre, which is the most advanced unit of its kind in the country.

Associate Professor Ruban Thanigasalam with the da Vinci robot.

While robotic surgery is fulfilling its immediate potential, Professor Bannon, Associate Professor Thanigasalam and other clinicians working in the area are mapping out the technology’s future, “The next question is whether we can go hands-off so robots operate by themselves,” says Professor Bannon. “Beyond that, can robots actually make decisions? We’re in the process of learning what the machine can learn.”

If robots can one day make clinical decisions, it will be through machine learning which is related to artificial intelligence. Once provided with vast amounts of relevant information – in this case, the performance of countless surgical procedures – the da Vinci system has the capacity to work out how to do the procedures autonomously.

This is where humans may have to adjust expectations in being comfortable with a machine making clinical decisions. Though in some ways, this is already happening. Some pacemakers now have a robotic element that monitors blood chemistry and flags when treatment may be needed. People who have diabetes also benefit from semi-autonomous devices assessing glucose levels and making decisions about insulin doses.

“Though actually, robotic systems don’t make decisions,” points out Professor Bannon. “They draw conclusions based on vast amounts of data that have been implanted. How far we can take this will be defined by the safety nets we put in place. And the safety nets will always be multi-layered and extensive.”

While fully autonomous robotic surgeons are still some time off, Associate Professor Thanigasalam sees a variation happening sooner, “Robotics could act as a fail-safe by overriding a surgeon in case of error. Then within maybe 20 years, we’ll likely see artificial intelligence within robotics,” he says.

Much more imminent is remote proctored robotic surgery. This is where a surgeon new to the technology in say, Wagga Wagga, can be supervised by a robotic surgeon in Sydney, and guided along the robotic surgery learning curve. With the horizons of robotic surgery widening, previously ambitious goals become achievable. As Professor Bannon says, “If you don’t set objectives, you’ll never know what’s possible.”

Certainly, the Hybrid Theatre is working towards becoming part of the global development of new technology in surgical robotics.

When SAM, perhaps clumsily, name checks the novel Brave New World to express the world-changing potential of the technology, Professor Bannon smiles widely and instead references a 1966 science fiction film where tiny scientists travel through a human body: “We think of it more as a fantastic voyage.”

Help people live longer and healthier lives

To learn more about the University’s groundbreaking medical research or help advance the work, please call Lachlan Cahill on +61 2 8627 8818 or email development.fund@sydney.edu.au

Written by Gabriel Wilder

Photography by Stefanie Zingsheim