Playing Beatie Bow brought to thundering life in a joyous stage play

Review: Playing Beatie Bow, directed by Kip Williams.

Playing Beatie Bow is the coming-of-age story of the teenage Abigail who, from her home in Sydney’s The Rocks, slips back in time to 1873. Here, she is taken in by the Tallisker/Bow family, immigrants from the Orkney Islands who run a confectionery shop. Abigail finds herself cast as the mysterious “Stranger” — the subject of a Tallisker family prophecy — which she must enact before she is able to return to her own time.

In adapting Ruth Park’s 1980 novel for the stage, Kate Mulvany carries forward Park’s detailed, loving attention to the city of Sydney and the lives that play out within it. Her adaptation thrums with heart, humour and a sense of creative legacy.

Ruth Park’s long and distinguished literary career began at the Auckland Star in the 1930s. In 1942, she moved to Sydney, the city which she would go on to capture with such verve and particularity. By the time of her death in 2010, aged 93, she was one of Australia’s most loved and successful authors.

Set where it plays, Playing Beatie Bow captures the spirit of The Rocks. Photo: Daniel Boud/Sydney Theatre Company

Park’s skill in writing for young adults was to portray the emotional intensity of adolescence alongside a broader sweep of time and history, and this production takes place in almost the very location in which the story is set. The qualities of The Rocks which so captivated Park — the steep topography, the narrow terrace houses, the crooked laneways — still produce a sense of a lingering past.

Many in the audience would have travelled through these streets to arrive at the theatre. There is a clear delight in this proximity, and the opening scenes set in the present day further develop this rapport, referencing the pandemic, distractions of social media, and that inevitable Sydney topic: the excesses of the city’s real estate.

History through present eyes

Names and objects are powerful in Playing Beatie Bow. In Park’s research for the novel she compiled long lists of potential Victorian-era names, deliberating over which would best carry the distinctions of her characters.

Park was rigorous in her historical research, with a particular interest in seeking out the everyday details of nineteenth-century working class life in Sydney. The heavy 19th century garments, chamber pots, ceramic “hot-pig” water bottle and the glass jars of boiled lollies work to as veritable effect on stage as they do in the novel. These details are highlighted in David Fleischer’s spare, dynamic set design.

Small touches like the glass jars of boiled lollies capture our imagination of the 19th century. Photo: Daniel Boud/Sydney Theatre Company

Mulvany’s inclusion of Aboriginal characters, language and recognition of country is a striking addition to Park’s original story.

In the present day, Abigail (Catherine Văn-Davies) visits her Gadigal neighbours, greets them “worimi”, and knows The Rocks equally as Tallawoladah.

In the 19th century, Abigail continues this connection with the Tallisker’s neighbour with whom she strikes up a friendship. Mulvany converts Park’s characters of the Chinese laundrymen to Johnny Whites (Guy Simon), an Aboriginal laundryman.

Through Whites the trauma and fracture of colonial dispossession for Aboriginal land and people is given voice.

Legacies of women

As Abigail and Beatie (Sofia Nolan) compare observations of each others’ times, Beatie expresses bemusement over the “palm-books” everyone in the future is looking down at and examining with such intensity. What book must it be, Beatie muses, maybe the Gospels?

This is Mulvany, but so absolutely in line with Park’s sensibilities I imagined her laughing along with the audience.

The cast of nine, who play 60 characters between them, revel in their portrayal of these time disjunctions, and in delivering the Tallisker’s Scots vocabulary. Mulvany takes one term in particular, spaewife, as a letimotif in the production.

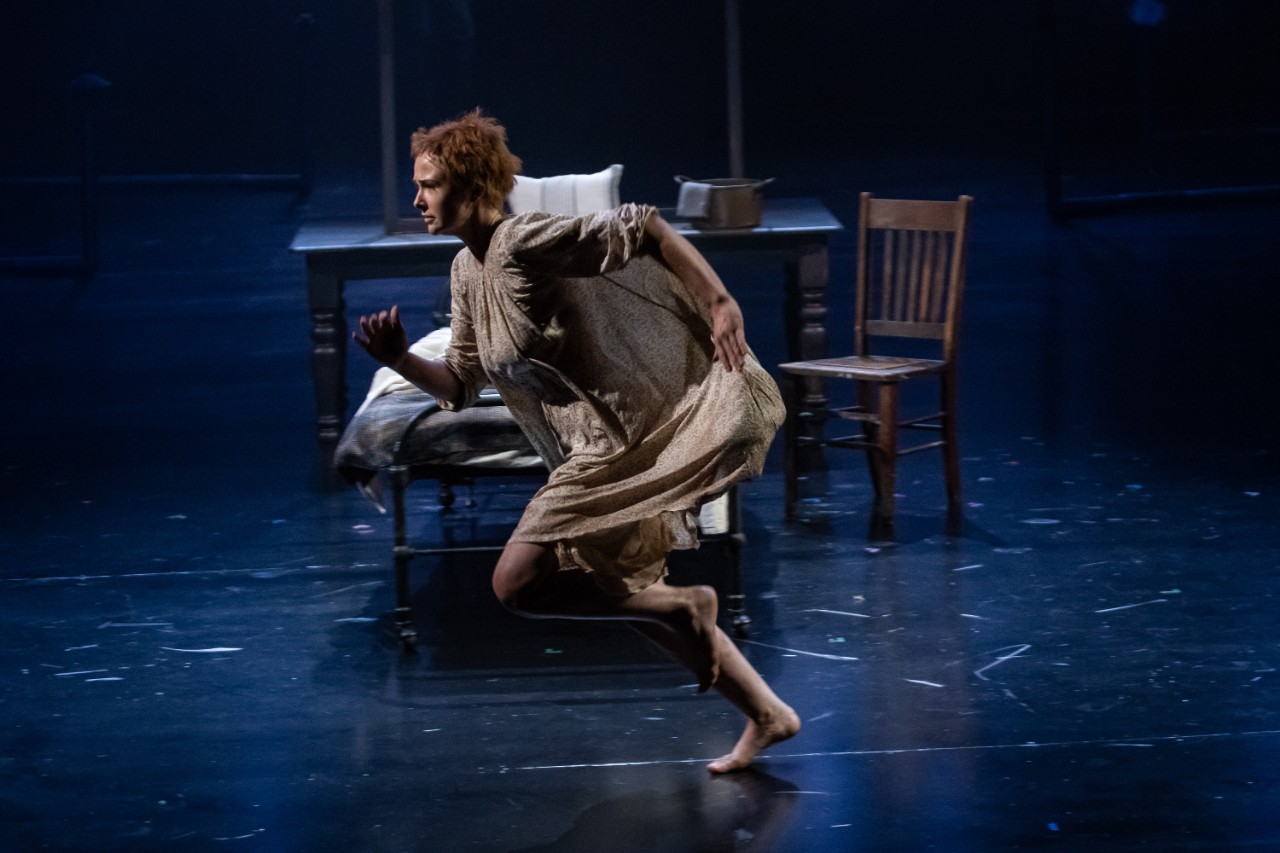

Throughout the book and the play, conversations reverberate between generations of women. Photo: Daniel Boud/Sydney Theatre Company

In Scots, a spaewife is a fortune-teller; a woman possessing a magic enabling communication across time. The Talliskers call it The Gift and it is carried by Granny (Heather Mitchell), the family’s matriarch.

Repeated in speech and song throughout the play, this word takes on an symbolic presence. In a story so much about legacy — particularly the connections and lineages that connect women — spaewife becomes broadly symbolic of women’s power.

This power radiates through the play, in the connections between characters and generations, and in between Park and Mulvany as writers.

Beatie, played here by Sofia Nolan, has an energy that reverberates through the decades. Photo: Daniel Boud/Sydney Theatre Company

There is no better embodiment of this power than in Beatie, played with an electric intensity by Nolan. Her force as a character is her quick tongue and determination to live a life greater than what is prescribed for women of her time.

The character of Beatie Bow was inspired by a girl in a 1899 street photograph from The Rocks, which Park came across in the 1940s. She describes the scene in her autobiography, Fishing in the Styx (1993): how she returned again and again to look at this “sharp-faced” girl who carried a defiant expression. The girl seemed to be speaking to her through time, challenging her not to take her for less than she is.

30 years later, Park wrote Playing Beatie Bow. Now, 40 years on again, through Mulvany’s fierce and fond version for the stage, Beatie’s voice speaks to us with a renewed energy.

Playing Beatie Bow is at Sydney Theatre Company until May 1.

Dr Vanessa Berry is a lecturer in Creative Writing. This review was first published in The Conversation as Playing Beatie Bow is Brought to Thundering Life in Joyous Stage Production. Find out more about the Master of Creative Writing. Top photo, actors Sofia Nolan and Catherine Văn-Davies in Playing Beatie Bow. Photo: Daniel Boud/Sydney Theatre Company.