Restricting welfare payments reduces Indigenous school attendance

Welfare quarantining, also known as ‘income management’, is aimed at improving child welfare in Australia. Yet new University of Sydney research, in collaboration with the Darwin-based Menzies School of Health Research, shows restricting welfare payments can have the opposite effect.

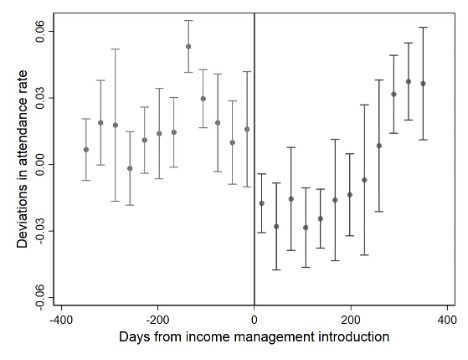

Researchers at the School of Economics studied the impact of the 2007 introduction of income management into remote Aboriginal communities in the Northern Territory. They found it reduced children’s school attendance during the first five months by an average of 4.7 percent.

“The results surprised us,” said co-author, Professor Stefanie Schurer.

“As for the reasons behind them, we found financial disruption and increased family discord may be responsible.”

School attendance eventually returned to initial levels but there was no further improvement.

Researchers say the results have continued relevance, given currently there are ongoing income management with even stricter rules in communities in the Northern Territory and at trial sites in other jurisdictions,

The study was published in the Journal of Human Resources.

Constrained welfare, less school

Using records provided by the Northern Territory Department of Education, the researchers sampled 9,162 students enrolled in grades 1-12, from 130 different schools, between 2006-2009 (inclusive).

They found that income management reduced existing poor average school attendance rates of children in these communities.

Previously school attendance rates were 63.7 percent (primary) and 57.9 percent (secondary). Girls were slightly more likely to attend school than boys (64.1 versus 61.3 percent).

After income management was introduced, these rates fell by an average of 4.7 percent across the board.

Professor Schurer said: “The drop in attendance was not confined to students who already had poor attendance. Even students who were more likely to regularly attend school attended less.”

Drawing on the staggered roll out of the policy, the researchers were able to isolate the effect of the income management reform from other factors they may have caused school attendance to drop.

They also ruled out that other components of the Northern Territory Emergency Response or changes in family mobility might have influenced the negative results.

Financial disruption, ‘humbugging’, and other issues

The researchers suggest that household financial disruption was a likely explanation for the attendance impact of the policy.

In some cases, welfare payments were hard to access or mistakenly suspended, leaving families scrambling, some even travelling from their remote locations to the nearest Centrelink to attempt to sort out their benefits.

This stress, the researchers say, likely impaired family functioning, again leading to school absences.

“Being preoccupied with pressing budgetary concerns leaves fewer cognitive resources available for decision making, and family support of children attending school,” Professor Schurer said.

Children missing school was just one side effect: they were also more likely to be involved in or upset by family arguments. In addition, increases in petty theft were reported, as well as an increased risk of ‘humbugging’ – relatives asking women and elders for money; a practice that income management aimed to reduce.

“This aspect of the policy was poorly received, as remote Aboriginal communities are highly collectivist and resource sharing is an important social institution,” Professor Schurer said.

Could cash transfers help?

A key question for policy makers and researchers is whether restricted welfare policies, such as income management, are preferable to other forms of conditioning welfare payments or interventions to achieve better outcomes for children. Income management is a costly policy.

For example, between the 2007-08 and 2009-10 financial years, income management in Australia cost AUD $451 million to administer (approximately $20,700 per income-managed person).

“The key question for policy now is to what extent is this cost offset by robust evidence of social benefits, or whether these resources could be redeployed to more productively enhance the wellbeing of Indigenous Australians,” Professor Schurer said.

About the 2007 income management scheme

Initiated by the Australian government in an effort to reduce the behavioural causes of disadvantage, income management required half of welfare payments to be quarantined for expenditure on priority needs. Its goal was to “stem the flow of cash going towards substance abuse and gambling and ensure that funds meant to be for children’s welfare are used for that purpose”. Boosting school attendance rates in the Northern Territory was not a formal policy goal, however it was an expected outcome.

The policy exclusively targeted Aboriginal communities, 65 percent of which were reliant on welfare as a main income source. It formed part of the Northern Territory Emergency Response, which was enacted in response to a report documenting child maltreatment and family violence within these communities.

The scheme continued in specific communities and remains present today on a rolling, ad-hoc basis. It is unique to Australia.

Declaration: The authors acknowledge funding from an Australian Research Council (ARC) Discovery Early Career Research Award DE140100463, an ARC Discovery Grant DP140102614, the Centre of Excellence for Children and Families over the Life Course (project number CE140100027), and a University of Sydney SOAR Fellowship (2017-2018).

The research team declares that it consulted with Prime Minister & Cabinet December 2017 and made a submission to and gave witness in the Senate Inquiry on the Social Security (Administration) Amendment (Income Management to Cashless Debit Card Transition) Bill 2019 with the Community Affairs Legislation Committee (LINK), 23 September 2019.

Hero image: Yaruman5 via Flickr.