SILLIAC: the machine that brought Australia into the computer age

The world had few computers but Sydney had the best

A horse-racing benefactor with an interest in science made one of Australia's first, and then most powerful, computers possible.

It’s a story that’s easy to love. It was the early 1950s and the University wanted to build one of the first and most powerful computers in the world, SILLIAC. But funds were short and it was only built because the race horse of a prominent donor had just won the Melbourne Cup. No Melbourne Cup win, no SILLIAC.

A donor with a passion for science

The truth is a little less cinematic. The donor, Adolf Basser, wasn’t a ‘colourful racing identity’. He was a man of modest disposition who happened to love horse racing: even more so when his horse, Delta, won the Melbourne Cup. But this was two years before he contributed to SILLIAC. In fact, Basser, who’d made his fortune through the jewellery business, was a long-time philanthropist supporting many causes, but he had a particular interest in science.

SILLIAC was just the sort of thing that would catch his eye, especially since the project was pitched to him by one of the University’s most charismatic and spirited characters, Harry Messel. Basser gave the modern equivalent of $4 million.

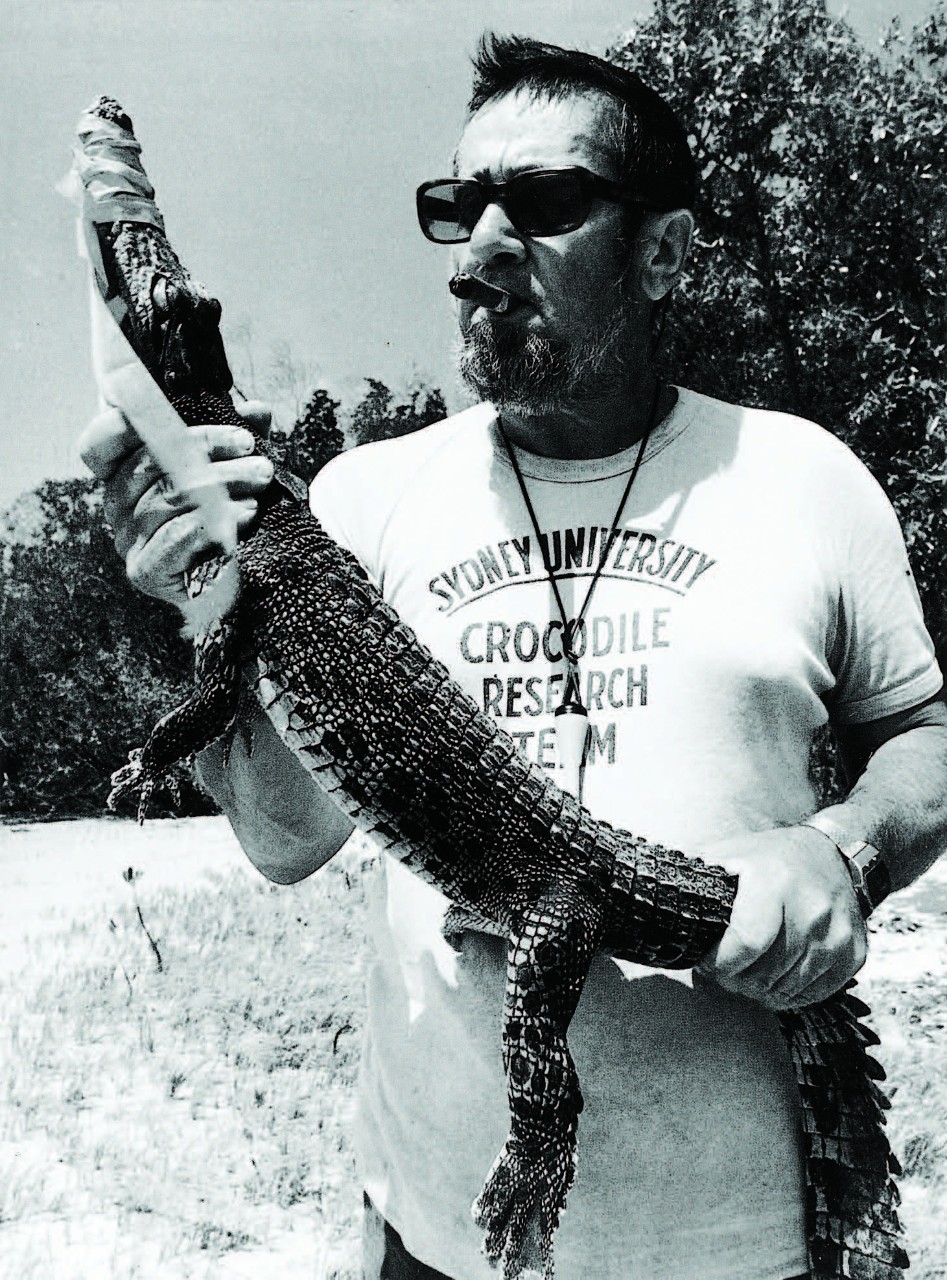

One of the University's most spirited characters, head of School of Physics, Harry Messel, who also had an interest in conserving wildlife. (Photo supplied by Faculty of Science).

Securing funding to create the Nuclear Research Foundation

Hailing from Canada, the cigar-smoking Messel became head of the School of Physics in 1952, when he was just 30, little knowing his tenure would last 35 years. He was to completely transform the department, but one of his first adventures was meeting the fearsome media mogul, Sir Frank Packer (father of Kerry and grandfather of James), to ask for money to establish the Nuclear Research Foundation (now the Physics Foundation) within the School of Physics.

Sir Frank asked what he would get out of the deal. “Absolutely nothing,” answered Messel. Messel got his money.

In establishing the Nuclear Research Foundation, Messel knew his research ambitions for the place would need serious computing power (or at least, the best that computers in the 1950s could offer). He estimated that just one of the necessary calculations would take people using desk calculators 2000 man years.

At that time, there were just a dozen computers in existence worldwide, and the Illinois Automatic Computer (ILLIAC), built by the University of Illinois, was considered the best. That said, it was a beast that comprised 2,800 vacuum tubes and weighed nearly 5 tonnes. Like all the computers at the time, it was ‘developmental’. Ideas around intellectual property were more relaxed then than now, and Illinois University was happy to share their ILLIAC blueprints, if Sydney shared its own advances on ILLIAC with them.

What the SILLIAC computer did in its 14 year life could be done on today's smartphone in minutes.

There was a great deal of information exchanged in both directions as ILLIAC became the Sydney version of ILLIAC, or SILLIAC.

All this was never going to be cheap. At the time, a Sydney suburban house cost about £3,500. It was estimated that SILLIAC would cost ten times more, or £35,000. Though, as is the way with these things, SILLIAC eventually cost £75,000.

Too big for your pocket. The SILLIAC computer was 2.5m high by 3m wide and required its own room in the Physics Building, plus two more rooms for suppport equipment. (Archives photo G77_1_2117)

A triumph for its time

For that money, the world welcomed probably the most powerful computer it had ever seen; it was certainly an advance on ILLIAC. There was little in the way of miniaturisation though. At 2.5 metres high by 3 metres wide and 0.6 metres deep, SILLIAC took up most of a room in the Physics Building, plus a room for a power plant, plus a room for cooling.

In contrast, and by modern standards, its performance was modest. The information it could store would amount to less than a second of an MP3 music file and what SILLIAC did over its 14 year life, could probably be done by a smartphone in under a minute.

SILLIAC ran Australia’s first computer payroll system for the then Postmaster-General's Department (now Australia Post).

At its peak SILLIAC ran 24 hours a day, seven days a week, and was used by more than 2,000 people. (Archives photo G77_1_2126)

SILLIAC's legacy

The first scientific calculation using SILLIAC was carried out by PhD student Bob May in June 1956, three months before the official opening. The machine would be a seismic advance in the Australian and world computer scene, and government and industry started asking what it could do for them.

SILLIAC ran Australia’s first computer payroll system for the then Postmaster-General's Department (now Australia Post). It was used by organisations like Woolworths, Snowy Mountains Hydro-electric and banks, who then went on to buy their own computers. It also saved University researchers many thousands of hours of laborious calculation. Along with all this, some of Australia’s earliest IT professional developed their craft by working on SILLIAC.

As computer advances accelerated, SILLIAC was eventually left behind. It was turned off in 1968 and dismantled. Only a couple of fragments still exist the Chau Chak Wing Museum. Still, it ran a great race.

Parts of SILLIAC are now on display at the Chau Chak Wing Museum.

Written by George Dodd for the Sydney Alumni Magazine, with thanks to Associate Professor Robert Hewitt, previous Director of the Science Foundation for Physics.